OPINION:

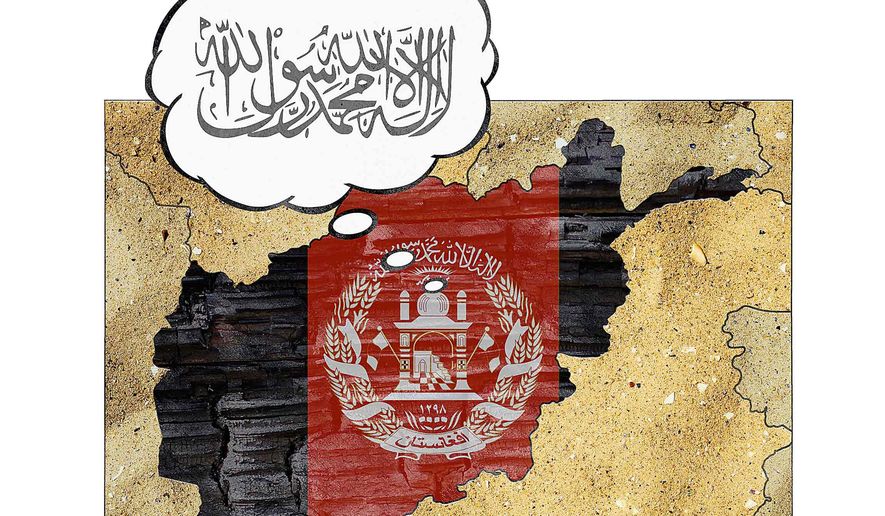

With the second round of peace talks between the Afghan government and the Taliban just around the corner, many Afghans fear the compromises that lie in store — reversals on gains in women’s rights and education, for instance. But others recall that life under the religious dictatorship wasn’t without its benefits, and wonder if such compromises aren’t a price worth paying.

Just to be clear, few Afghans want to see a return to the draconian interpretation of Islam that banned music, TV and dancing. Many still remember the stonings, lashings and beheadings that were imperative pre-game viewing at Ghazi Stadium. Hazaras, a Shia ethnic minority hated by the Taliban, have a uniquely clear-eyed memory of Taliban oppression. Not to mention Afghan women, who were removed from schools, ordered into burkas and put under house arrest.

But Afghans also remember that time as one when the machinery of government ran the way it was supposed to. Government was small, easy to navigate, and problems could be solved without the bribes that are endemic today. Crime was almost non-existent, the only murders one heard about were carried out by the Taliban, and you could leave your house without locking the door (though, with most forms of entertainment banned, there was probably nowhere you wanted to go).

Much of the chaos of contemporary Afghan life can certainly be traced to the Taliban. But not all of it. Afghans feel dismayed by the failure of their government to uphold the rights of women. Take the recent case of Farkhunda Malikzada, who in March was brutally murdered by an angry lynch mob on a false charge of burning the Koran. Justice was meted to her killers swiftly and transparently. And then a few weeks later, in an irregular closed-door session, an appeals court commuted all of the sentences.

When three women were proposed for Cabinet positions under the new government, Parliament rejected all three of them. And last month, with the opportunity to appoint the first-ever woman to the Supreme Court, Parliament blew it again, asking the president to send them another candidate. Child brides continue to be married off to old men — even though Afghan law forbids it — and those who try to escape are treated as moral criminals. (Human Rights Watch notes that 95 percent of all girls in Afghan prisons are held on “moral crimes”).

Bacha bazi, the tradition of warlords abducting young boys into sexual slavery, all but disappeared under the Taliban, who penalized offenders with death. But in recent years the practice has seen a revival. When a gunfight erupted this week at a Baghlan wedding between rival warlords, killing more than 20 guests, witnesses claimed that it stemmed from an argument over which warlord had the most desirable boy. Bacha bazi is also illegal, but the law is rarely enforced. When the United Nations appealed to President Hamid Karzai to halt the practice a few years ago, his reply was laconic. “Let us win the war first, then we will deal with such matters.” The current government has been silent on the subject.

In addition to making laws it doesn’t uphold, the Afghan government has been slow to invest in the kind of infrastructure that improves the lives of its people. While there is no shortage of construction of new mosques, Kabul is one of the only world capitals with no public sewage system. Garbage pickup is rare, and trash in most neighborhoods is piled on street corners or dumped on local riverbanks to await pickup. Twice as many Afghans die as a result of Kabul’s polluted air (which is worse than Beijing’s) than die from war-related incidents.

Social stability will be a critical factor in the National Unity Government’s ability to maintain its legitimacy. This means creating a judicial system that has integrity and a bureaucracy that functions as it should. And it means bringing women into positions of power and leadership.

Make no mistake: The Taliban was not a force for good in Afghanistan. Its rule was characterized by violence, terror and repression. But it created a system that worked, and for all its depravity, runs the risk of being held up as responsible for a golden age — if the present government doesn’t learn to embrace the rule of law and address the quality-of-life issues that directly affect the well-being of its people.

• Will Everett is an American writer and aid worker living in Afghanistan. He is the author of “We’ll Live Tomorrow,” which will be published in October.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.