OPINION:

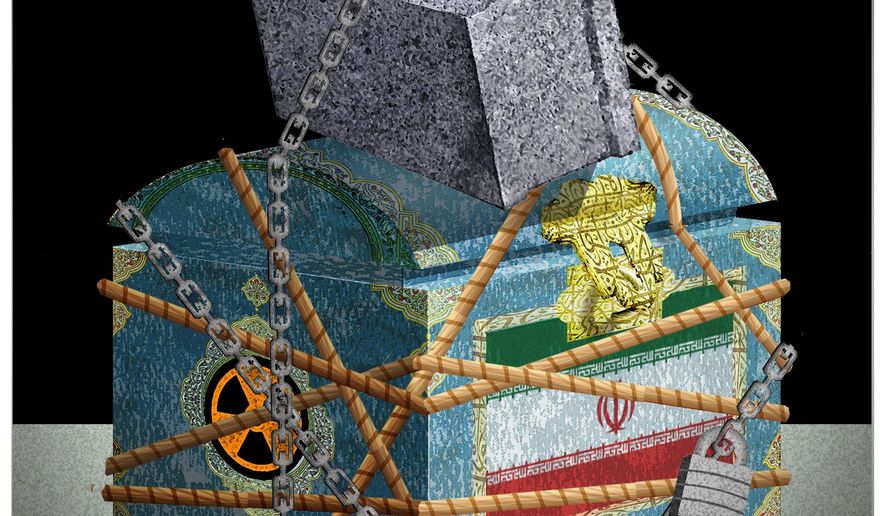

How would the prospects for stability in the Middle East be affected if Iran were to succeed in its effort to become a nuclear power? In what ways might we expect Iran to behave differently?

The behavior of the Soviet Union in the late 1970s is instructive on this point. Despite signing the 1972 SALT I Agreement with the United States, which put restraints on strategic nuclear forces, the USSR soon began to violate several of its tenets and to establish an advantage in ICBM warheads. Before long it had established a comfortable margin of superiority over the United States. Then, secure against any plausible threat, it became more willing to take risks to expand its influence in various parts of the world. We recall well those years from ’75 to ’80 in which the Kremlin’s support for so-called wars of national liberation enabled them to exert a prevailing influence in country after country — Angola, then Ethiopia, South Yemen, Mozambique, Afghanistan (following an invasion by more than 100,000 troops), and ultimately, Nicaragua. Not until the early ’80s, as the United States restored its will to oppose Soviet expansion, did the Kremlin change course.

For several reasons it appears almost certain that Iran will manage to continue its clandestine program to develop a nuclear weapons capability in the years ahead. The stated intention of the European parties to the “framework” that was recently concluded is to hold Iran’s feet to the fire during the 90-day negotiating period toward a formal agreement. However, their commercial interest in re-entering the Iranian market and the muted voice of its political leadership will lead to backsliding on negotiating terms essential for catching and dealing with violations. In a recent critique of the state-of-play in the negotiation with regard to verification, Charles Duelfer, who led the United Nations Iraq Survey Group investigation of the scope of Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction program, had this to say about no-notice inspections: “In my experience in Iraq, even with all the measures [the United Nations Special Commission] took (which were far more intrusive than those being reported from Lausanne), I doubt there was ever a truly ’surprise’ inspection.”

It ought not need saying, but history tells us that first-generation revolutionaries such as Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei never break faith with their original purpose; think Mao Zedong, Ho Chi Minh or Vladimir Lenin. They cannot afford to do so. After all, they rallied a nation to their purpose, and called forth a generation or more to risk their lives for their cause. They cannot blithely awaken one day — after more than a half-million sons, husbands and fathers have given their lives — to say, “I’m sorry but I’ve decided to abort the theocratic crusade idea; I’m going to rethink this whole thing.” Certainly, Ayatollah Khamenei hasn’t given even the slightest indication that he intends to do so.

In the negotiations between now and the end of June, the European allies will look to the United States to lead the negotiation. President Obama has expressed his intention to take any agreement reached to the United Nations — not the U.S. Congress — to achieve its “validation.” Given the ambivalence of each of the other permanent members of the U.N. Security Council, it will be endorsed unanimously. Soon thereafter, current sanctions will be relaxed, Iran will begin to export oil and recover economically. How will this turn of events affect Iran’s behavior?

Consider the opportunities open to Iran in circumstances where even before it has actually built a nuclear weapon, it has been given credit for being on the way to doing so by its neighbors. Iran will enjoy far greater deference and willingness to help advance her purposes by its Shia allies in Iraq, Syria and subgroups (i.e., Hezbollah and Hamas). It’s not a reach to anticipate a step-up in cross-border harassment of Israel by Hezbollah and Hamas, the provision of additional support to the Assad regime in Syria and to Shia militias in Iraq. Such actions will stimulate grave concern among Arab states across the Gulf and likely lead Saudi Arabia, and perhaps Qatar, to launch their own nuclear programs. Such a scenario is not far-fetched.

What, then, should the United States do? Several measures come to mind:

First, open talks with moderate Muslim countries (i.e., Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Jordan and members of the Gulf Cooperation Council) toward formation of a regional collective-security organization. Such an organization could coordinate intelligence-gathering, and through joint planning, put in place other measures to establish a credible deterrent.

Second, work with Saudi Arabia and its OPEC colleagues to maintain the price of oil as low as possible so as to inflict maximum pressure on Iran’s economy.

Third, invite constructive proposals on a bilateral basis from Israel for how it could enhance the security of the region.

Fourth, re-establish the U.S. Information Agency and begin broadcasting into Iran (Note: 70 percent of Iran is under the age of 30 and very open to hearing truth from the West).

If there were a positive lesson to be learned from the experience of the past two years, it concerns how well sanctions have worked. Iran’s economy is truly in a free fall today and the stresses being experienced at the grass roots of Iranian society have been the leading reason Iran came to the table in Lausanne and stayed. Keeping the sanctions in place at least through the first two years of any agreement so as to have demonstrable evidence that Iran is not violating its terms would be entirely reasonable. We have the diligent professional work done by Mark Dubowitz at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies to thank for developing much of the substance that found its way into the statutes and sanctions policy — both here and in Europe.

• Robert McFarlane served as President Reagan’s national security adviser.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.