ANALYSIS/OPINION:

Pretty historic moment: A president personally committed to, and heretofore politically rewarded for, ending wars and reducing American involvement abroad gets his own “My fellow Americans” moment.

There’s a lot to unpack from that moment, but this column is called Inside Intelligence, so let’s stay in that lane.

We now have an objective: We are going to degrade and destroy ISIS so that it no longer represents a threat to the United States or its friends. And we have the components of a strategy: American air power, allied ground forces and a commitment to pursue ISIS wherever it exists.

All of that seems clear enough, and clarity is always good. There has been a running battle the past few months over what kind of warning the intelligence community gave policymakers about the rise of ISIS. The finger-pointing in both directions has been unseemly. But (in the view of this former intelligence officer) the three-month gap between the fall of Mosul and the delivery of the president’s strategic vision last night suggests any shortfalls had more to do with policy clarity than intelligence warning. With Iraq’s second-largest city under terrorist control, how much more strategic warning do you need?

But things are more clear now strategy-wise, and, with that in hand, intelligence experts can develop a list of PIRs — priority intelligence requirements — the things we need to know to make the strategy work. From there collection plans — complex schemes to acquire the information from a variety of sources — will be developed.

Some general observations on that. We will flood the zone with ISR — intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance vehicles — including UAVs such as Predator, Reaper and the like. We know how to do this. We’ve gleaned exquisite intelligence from these platforms in Iraq, Afghanistan and elsewhere. Multiple agencies around town are already designating people to form the analytic back end for what will be a flood of streaming video and intercepted communications.

The caution here is the need for bases in places like Iraq, Kurdistan, perhaps Jordan, even Saudi Arabia. The bases have to be secure, so we should drop the near mantralike repetition of the obviously inaccurate “no boots on the ground.” That’s not a strategy; it’s a bumper sticker. The president has already directed more than a thousand U.S. military personnel back to Iraq. They are armed, have body armor and most certainly are wearing boots.

That number is bound to increase. There won’t be brigade combat teams conducting maneuver warfare in the desert, but stand by for 5,000 troops or more as we tote up resources for force protection, special forces raids, training, logistics, targeting, imbedding and the like.

A second caution for ISR: The air defense environment may not be as permissive as we experienced in, say, Afghanistan. ISIS has gotten its hands on some Iraqi heavy weapons and almost certainly has MANPADs. Syrian air defenses, if they chose to engage, could also be troublesome, although Damascus should be dissuaded by the nature of our targeting (against ISIS) and the very real promise of retaliation.

Other national assets will be tasked for collection as well, especially for SIGINT. There will be challenges. ISIS is a learning enemy, and former Deputy Director of NSA Chris Inglis says that they have gone to school on the documents released by Edward Snowden and have changed their communications practices.

That puts an increased premium on HUMINT, and here we will have to team with friends. Nothing new there: CIA nurtures these kinds of relationships globally. CIA relies on a partner’s focus, linguistic agility and cultural depth; in return, the partner benefits from CIA’s resources, technology and global view.

Identifying worthy intelligence partners in the Syrian opposition will be a heavy lift but, one hopes, not an impossible one. The Kurds and Jordanians certainly come to mind. Not so much the Iraqis, since former Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki sacked a tough, professional intelligence chief, Mohammed al-Shahwani, in 2009. Mr. al-Shahwani was a hero in the war against Iran and later lost three sons to Saddam’s cruelty, but he was Sunni and, eventually, a casualty of al-Maliki’s sectarian agenda.

People like him would be invaluable now. The force that swept through western Iraq was spearheaded by ISIS but buttressed by Sunni tribes alienated by Baghdad’s heavy sectarian hand. One “advantage” of the slow U.S. response has been to allow the Sunnis to really get to know their new ISIS friends. The experience has not been a positive one. As we strike back in earnest, we will need exquisite intelligence to distinguish the irreconcilable from the merely angry.

Overall, the president’s announced approach Wednesday echoes classic counterinsurgency strategy. First, kill, capture or incapacitate insurgent leadership. The promise of strikes beyond merely the protection of key facilities like the Mosul dam should start to address that. Second, deny the insurgency a safe haven. That means Syria, and if ISIS in Syria continues to be off-limits, none of this is worth doing. Finally, a successful strategy needs to change the facts on the ground, the conditions that generated the problem in the first place.

That last task is obviously the toughest and will not happen quickly. Even near-term steps like nurturing a more inclusive Baghdad government will require deep insights into political dynamics there.

And what does the overall endgame look like? Here intelligence is going to have to provide insight well beyond just that needed to find, fix and finish terrorist targets. I don’t want to be overly dramatic, but Iraq and Syria are gone, and they aren’t coming back, at least not as centralized states. So what does the new equilibrium look like?

I can almost hear the opening line at the first deputies meeting convened to address that.

“Intel, why don’t you give us a laydown of what we’re dealing with here?”

“Well, Tony, in 632 there was this dispute “

If we are to avoid being trapped by that history, someone is going to have to explain it very, very well.

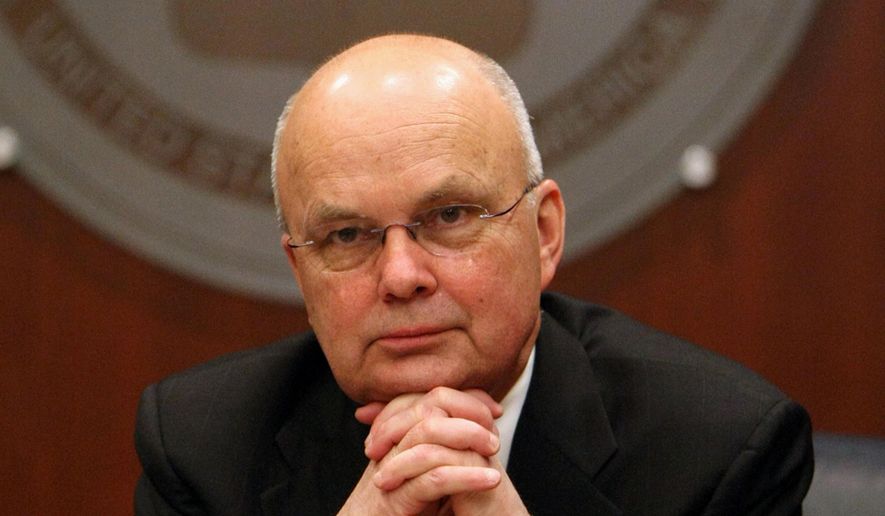

• Gen. Michael Hayden is a former director of the CIA and the National Security Agency. He can be reached at mhayden@washingtontimes.com.

• Mike Hayden can be reached at mhayden@example.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.