OPINION:

Nov. 21, 1620, was a bitterly cold day off Cape Cod — so cold that the sea spray froze on the coats of the ship’s passengers.

But this was minor in comparison with the other problems they had encountered since leaving Europe. For example, their ship, the Mayflower, was a wine carrier that had been poorly converted to passenger use. It was much too small for 102 people in addition to the crew and forced the mingling of individuals who had little in common with one another. Most passengers were hell-bent only on making money in the New World, while a minority, “the Saints,” as they would be derisively called, hoped to build an economically viable religious community unchallenged by English political authorities.

During the 66-day voyage, the Saints, subsequently dubbed Pilgrims, sang hymns, while the other passengers chimed in boos. To be sure, many had signed an agreement aboard the ship setting up a form of government in the new country, but there was squabbling over the details. The one redeeming aspect as the two groups moved ashore with the frozen sea spray on their coats was that the Saints gave thanks for finally reaching their destination dubbed Plymouth — a thanksgiving a year before its formal observance.

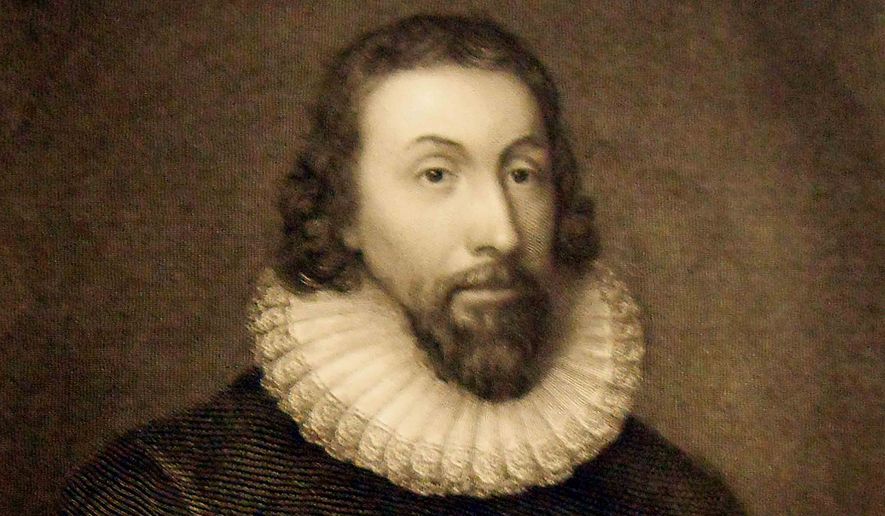

What followed in the weeks, months and years to come was an answer to their prayers, namely, that the initial adversity of living, first on ship and then in caves and shoddy wooden shacks, would develop into a religious community fortified by a strong private enterprise economy. The two leaders who accomplished these goals were governors, William Bradford of Plymouth and John Winthrop of the nearby Massachusetts Bay colony, founded in 1630, that eventually subsumed the smaller Plymouth settlement.

Bradford was 31 when he became governor of Plymouth for the first time. As a boy, he proved to be a maverick, deserting his family’s church for a separatist faith. As a man, he believed that idleness was religiously wrong and economically devastating. Because English officials began to persecute his sect, he and other church members fled to the more tolerant Holland, the center of Europe’s textile industry. Although Bradford received a family inheritance when he was 21, he was devoted to working for a living and became a master weaver. But Holland’s worldliness was too tempting for religious dissidents, especially children, and off they moved to America.

As governor, Bradford forged private enterprise principles into a colony bound by religious dogmas. Repudiating a backer’s loan requirement that the settlement own property only communally, he paid off the balance quickly with interest rates as high as 45 percent.

John Winthrop, like Bradford, came from a solid family that also provided him with an ample inheritance. He would study law, become a lawyer and justice of the peace and move to higher legal positions in London. He also became utterly bored. The one excitement in his life was his religious creed that, like Bradford’s separatism, had little in common with the prevailing Anglican mentality. Winthrop’s Puritanism stressed man’s quest for perfection, emphasizing to a lazy and indulgent world that good people could prevail by continual religious devotion and hard work, and build a model “city upon a hill.”

What sustained both Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay was that, thankfully, America could be carved into a better community for all, providing that elusive but mysterious challenge that was missing from the lives of so many in England. Not a single Pilgrim and only a few Puritans opted to return to the Old World. The Pilgrims, who lost half their population in the first year as a result of disease and starvation, said of themselves: “It is not as with other men, whom small things could discourage or small discontents cause to wish themselves home again.”

John Winthrop, like the Pilgrims on Nov. 21, 1620, celebrated his first Thanksgiving in one of his first letters to his wife: “I thank God. I like so well to be here, as I do not repent my coming: and if I were to come again, I would not have altered my course, though I had foreseen all these Afflictions: I have never fared better in my life, never slept better, never had more content of mind.”

Thomas V. DiBacco is professor emeritus at American University.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.