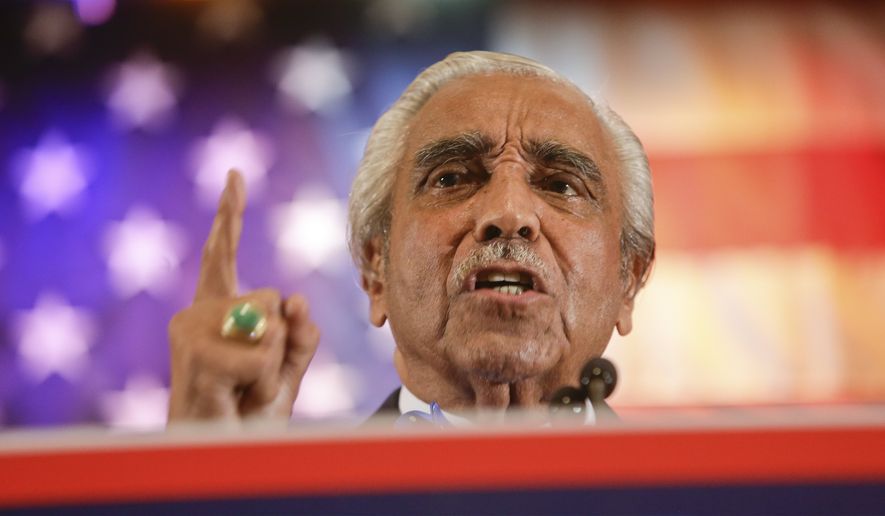

Rep. Charles Rangel went to a federal appeals court Thursday to try to have his 2010 censure from fellow members of Congress expunged, arguing the committee that investigated him was racist and violated his constitutional rights.

A lower court judge has already tossed Mr. Rangel’s case, arguing that his colleagues who censured him for ethics violations stemming from tax avoidance and use of public office to raise money for a private foundation were protected by the Constitution’s Speech and Debate Clause, which allows lawmakers to engage in their duties without having to worry about being sued.

But with the New York Democrat looking on from the front row, his lawyer, Jay Goldberg, told a three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit that the Speech and Debate clause can’t be used to justify Congress trampling on an individual’s due process rights.

“These are not procedural irregularities. These are of constitutional magnitude,” Mr. Goldberg said, recounting problems he said tainted the investigative committee that looked into Mr. Rangel’s behavior.

Judge Thomas B. Griffith said the courts usually see cases where members of Congress are arguing they are protected by the Speech and Debate clause, but in this case it’s Mr. Rangel who’s arguing his colleagues are not protected by it.

He prodded Mr. Rangel’s lawyer to say what is the actual harm that Mr. Rangel suffered.

The 22-term congressman was the chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, which means he was the country’s top tax-writer, when he admitted he failed to pay taxes on a villa he owned in the Dominican Republic. The House ethics committee also found him guilty of using his public office to solicit money for the Charles B. Rangel Center for Public Service at the City College of New York and failing to report income and assets on his congressional financial disclosure forms.

Mr. Rangel, though, argues that the four Republicans who served on the panel were given extra information that the four Democrats weren’t, in questionable communications that he says would have been clearly illegal if they had been sitting judges instead of members of Congress.

He argues that since the lawmakers were acting as judges in this case, they should be held to that standard, and because they violated his rights his censure should be expunged. Mr. Goldberg also told the judges that a former high-ranking staffer on the ethics committee had raised the possibility that racism played a role in the committee’s behavior toward Mr. Rangel.

Isaac Rosenberg, a lawyer for House Speaker John A. Boehner, who is the named defendant in the case, told the judges that they cannot peer too deeply behind the curtain into the inner workings of Congress.

He said the Constitution and Supreme Court interpretations of the founding document show that lawmakers and their staffers who are acting on their behalf cannot be questioned as to their motives or actions.

“The House conducts its business through its members and through its committees,” Mr. Rosenberg said.

He also said even outside of the Speech clause, Mr. Rangel’s censure is a “political question” issue, and courts have generally decided that they shouldn’t get involved in those kinds of cases, leaving them up to voters to resolve.

But Judge Patricia Millett posed a hypothetical, wondering whether judges could step in even if lawmakers censured or expelled a fellow member of Congress just because he or she was black.

Mr. Rangel himself had asked for the ethics investigation, believing it would clear him of the cloud of suspicion that had developed around him. But he was pressured to give up his position as chairman of the Ways and Means Committee anyway.

Mr. Rangel just won re-election to his 23rd term last week.

• Stephen Dinan can be reached at sdinan@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.