OPINION:

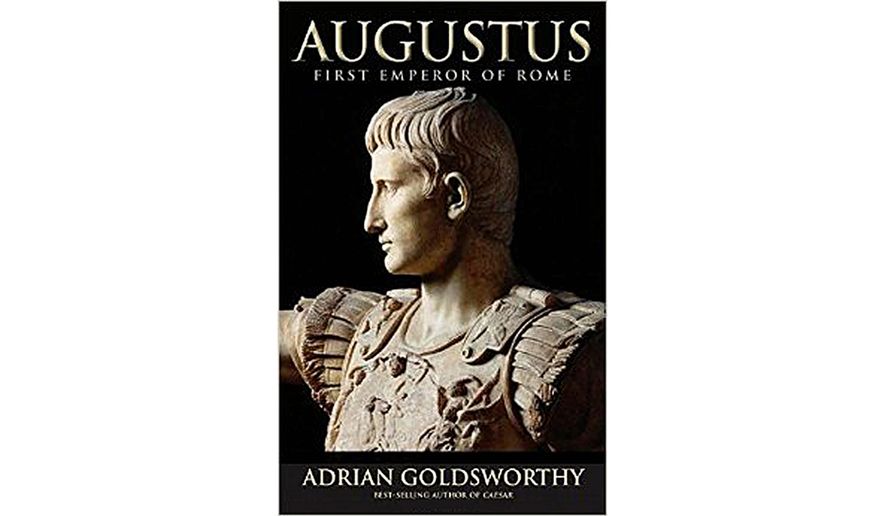

AUGUSTUS: FIRST EMPEROR OF ROME

By Adrian Goldsworthy

Yale University Press, $35, 624 pages

Caesar Augustus remains the person in the ancient world whose image is the most recognizable, surviving to the present day in statues, coins and frescoes. He was the Barack Obama of his day, except that he actually created significant and lasting accomplishments.

Adrian Goldsworthy’s prodigious biography of this first and greatest Roman emperor is thorough and well-researched. Casual readers of Roman history such as myself are probably most familiar with Augustus and his extended family through the novels of Robert Graves and the “Masterpiece Theatre” series that they spawned. Mr. Graves’ depiction of Augustus’ family filled with treachery and infighting among the emperor’s adopted sons, his wife and in-laws is less dramatic than what Mr. Goldsworthy portrays. Based on the fragments of history that survived the barbarian invasions, Mr. Goldsworthy’s depiction is a more plausible version.

Augustus was the adopted son of Julius Caesar. He was not a promising heir to the great conqueror’s legacy. Augustus was a sickly lad, but Caesar recognized his potential and ambition. Having no legitimate male children of his own, Caesar designated his grandnephew, also known as Octavian (he was born Gaius Octavius), as the heir to his estates. However, this bound the young man to avenging Caesar’s assassination at the hands of a group of ambitious Roman senators hoping to restore the old Roman republic that had been hopelessly compromised by nearly a century of discord and civil war. Octavian became a junior member of the triumvirate that set out to avenge the death of Julius Caesar.

The story of how this young man outwitted Mark Antony and a diverse group of other claimants to Caesar’s legacy takes up the first part of the book. The second section details how Octavius became Caesar Augustus and transformed a city-state that ruled Italy and a number of overseas possessions into a true empire with an efficient centralized bureaucracy.

Beginning with the suppression of Caesar’s assassins and culminating with his victory over his former ally Mark Antony, Augustus showed a flair for ruthlessness and ambition that marked him as a great practitioner of what would later become known as power politics. Augustus was not a brilliant tactician, but he inherited the money to buy many legions. He picked capable subordinate commanders and, when necessary, showed sufficient courage in combat to demonstrate the manly traits required of a Roman leader.

Augustus could be ruthless in his pursuit of power. By the time he became supreme ruler of Rome and its empire, all of his rivals were dead, intimidated or in exile. Some of the dead were not enemies, but rich neutrals, whose properties would fill his war chest.

The real story here is how well Augustus used power once he had it. For decades, he ruled wisely and well. He rebuilt Rome from a provincial and unimpressive town into the known world’s capital. He cultivated the arts and extended citizenship to provinces outside Rome, thus ensuring their loyalty for centuries.

What Augustus could not do was create a constitutional form of succession or control his unruly extended family. This was the seed of future turmoil in the empire. Augustus did not mean to create a dynasty, but the system he forged meant that his designated heirs created first a family monopoly on power and then a virtual market where whoever could buy the Praetorian Guard that Augustus created could claim supreme power.

While Augustus’ greatest failing was the failure to create a constitutional form of succession, the good that he did forged a legacy of civilization that preserved what was best in Greco-Roman Western practices and allowed the eventual rise of Christianity as well as the eventual European domination of the non-Mediterranean world.

Mr. Goldsworthy is a superb historian and talented writer. He has penned excellent biographies of Julius Caesar and Cleopatra. As a casual reader of Roman history, I appreciated the appendix, in which he identifies some of the complex offices that Roman leaders had to obtain in order to gain enough stature to be remembered by posterity. The book may be a tad too detailed for the non-academic reader, but it will likely join the pantheon of biographies of a truly great Roman leader.

One of the things that Mr. Goldsworthy reminds readers of is that human nature does not change. Augustus cultivated what passed for the Roman media as assiduously as any American politician today woos Fox News or CNN. One gets the impression that Augustus would have adapted well to 21st-century politics while still ruling wisely.

Gary Anderson, a retired Marine Corps colonel, is an adjunct professor at George Washington University’s Elliott School of International Affairs.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.