OPINION:

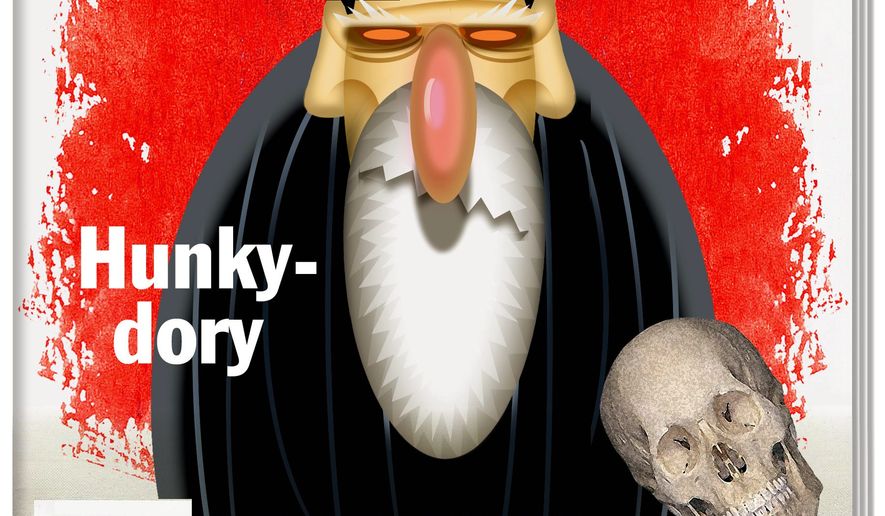

“The revolution is over.” When journalists at The Economist, one of the world’s most influential publications, run that headline on a cover story, “a special report” on the “new Iran,” you assume they have solid evidence to support their thesis.

You assume wrong. What The Economist presents instead are unsubstantiated assertions: “The revolutionary fervor and drab conformism have gone.”

And lame aphorisms: “Globalization trumps Puritanism even here.”

And platitudes: “In a highly educated and well-informed society, only so much can be imposed from above.”

And weird theories: “Pornography, although strictly banned, blazes a trail for freedom.”

Even The Economist’s history is fallacious. Readers are instructed that Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, leader of Iran’s 1979 Islamic Revolution, “was essentially an anarchist” who “despised state structures,” but who realized that the “gains of the revolution could be cemented only with the help of permanent institutions.”

Simply not so: Khomeini’s most important work may be “Hukumat-e Islami” — “Islamic Governance.” He famously declared: “Those intellectuals who say that the clergy should leave politics and go back to the mosque speak on behalf of Satan.” He preached that allegiance to Islam should replace patriotism — not just in Iran, but in all lands.

Ignoring all that (or perhaps ignorant of it), The Economist contends that Khomeini “mimicked America’s Founding Fathers, creating checks and balances and occasional gridlock.” I kid you not.

Summarizing how Iran became an Islamic republic, The Economist writes: “First came the courageous street protests during the 1979 revolution, then the infighting started. Thousands were executed, properties were seized, bread was short.”

In fact, after the Shah’s departure on Jan. 16, 1979, Khomeini returned from exile in France to a hero’s welcome. Before long, he turned on his non-Islamist supporters — democrats, socialists, communists and others who had naively believed they were valued members of a revolutionary coalition. Why use the passive voice to describe the executions, property seizures and food shortages? Is there any doubt as to who was responsible?

Could it be because even in “post-revolutionary” Iran, criticism of Khomeini, like criticism of Islam, can get a journalist thrown into the hoosegow? Washington Post reporter Jason Rezaian has been imprisoned since July, reportedly in solitary confinement. The Economist doesn’t mention him.

Coincidently, CNN culinary reporter Anthony Bourdain also presented a special report on Iran this month. It included an interview with Mr. Rezaian and his Iranian wife, Yeganeh Salehi, correspondent for an Abu Dhabi-based newspaper. Neither has been a critic of the regime. Mr. Bourdain is troubled by Mr. Rezaian’s incarceration (Ms. Salehi also was jailed, then released last month), but he doesn’t let that interfere with the story he wants to tell, which is similar to the story told by The Economist: Iranians, he is shocked to find, are friendly and hospitable, not revolutionary firebrands. From that he infers that the regime must be not so bad after all.

It’s an illogical inference. Does anyone think that the average North Korean would not be gracious toward an American? Does that lead to the conclusion that Kim Jong-un isn’t a despot?

The Economist says that Iran is no longer “seething with hatred and bent on destruction.” However, neither was it in early 1979 when I spent several months there covering the Iranian Revolution. Most people were eager to talk with me, but most people were not the angry jihadis who, in the fall of that year, seized the U.S. Embassy and for 444 days abused the diplomats they took as hostages.

Both The Economist and Mr. Bourdain are concerned about the impact of sanctions on Iran’s economy. Both give short shrift to what provoked the sanctions: The regime’s illicit nuclear-weapons program. The Economist says of this program: “Many regard it as a symbol of national strength at a time of perplexing social changes.” Ah, yes, what better fortifies one against perplexing social changes than nuclear-armed missiles with “Death to America!” painted on their sides?

The Economist reinforces all the standard media memes. Iranian President Hassan Rouhani is a “moderate” battling “hard-liners.” Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif is “dovish.” Qassem Suleimani, the commander of the Quds Forces responsible for the deaths of hundreds of Americans in Iraq, is merely the “bete noire” of the American armed forces.

As for the current supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, “he sees himself less as a decider than a referee.” Anyone who thinks Ayatollah Khamenei won’t be the one who gives thumbs up or down to a nuclear-sanctions deal has been drinking pomegranate Kool-Aid.

The special report appears at an inconvenient moment. The Assad regime in Damascus, Iran’s client, continues to kill tens of thousands of Syrian civilians. Iranian-backed rebels have overrun the capital of Yemen. In recent days, Ayatollah Khamenei has repeated his call for the “annihilation” of Israel. A young woman has been sentenced to death for defending herself from a rapist. Even Iranian dog lovers could face 74 lashes — because dog ownership “harms the country’s Islamic culture.”

A note of what’s meant to be even-handed optimism concludes the special report: “Both sides appear committed to reaching a deal” and both want “to improve relations at the same time. Previously, one or the other was always on the warpath.” Such a deal would bring Iran “a step closer to fulfilling its ambition of leading other nations in the region.”

Leading and ruling are distinctly different concepts. The sophisticated journalists at The Economist would not normally confuse the two. Why, when it comes to the Islamic republic of Iran, have they made an exception? I can think of a number of explanations — none of them journalistically defensible.

Clifford D. May is president of the Foundation for Defense of Democracies and a columnist for The Washington Times.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.