It probably didn’t factor into his decision, but President Obama’s recent diplomatic breakthrough with Cuba could have the side benefit of re-establishing normal relations with one of the world’s great chess-playing cultures, a country with a rich history in the game that has long punched above its weight in global chess circles.

Cuba, of course, produced the player who may be the greatest talent the game has ever seen, Havana-born Jose Raul Capablanca, who was world champion from 1921 to 1927. But the island’s chess tradition extends far beyond one great player.

Contemporary accounts say chess was being played on the island shortly after Columbus first made landfall in October 1492. The Turk, the famous chess “automaton,” visited the island on its last world tour in the 1820s, and America’s first world champion, Paul Morphy, stopped in Havana to take on the local masters in two visits in 1862 and 1864. Bobby Fischer famously competed in the 4th Capablanca Memorial in 1965 by telex from the Marshall Chess Club in New York after being denied a visa by the State Department to compete in person. (He finished second behind Soviet former world champ Vasily Smyslov, whom Fischer defeated in their individual game.)

Three world championship matches have been held in Cuba, including Capablanca’s win over Emanuel Lasker and two tough title defenses by Wilhelm Steinitz against his great Russian rival Mikhail Chigorin in 1892 and 1894. Cuba also hosted the 17th FIDE Chess Olympiad in 1966 — where Fischer was allowed to compete.

Cuba is easily the strongest chess-playing nation in the Western Hemisphere after the U.S., with its men ranked 18th in the world by FIDE and its women 16th. The country has produced two world junior champions, Walter Arencibia Rodriguez in 1986 and GM Lazaro Bruzon in 2000. Bruzon is now the Cuba’s second highest rated player, behind GM Leinier Dominguez Perez.

(Much of the information here comes from a fine historical review by Bill Wall at Chess.com.)

Juan Corzo was one of Cuba’s first great players of the modern era, unfortunately best remembered today as the player Capablanca supplanted on his meteoric rise to greatness in the first decade of the 20th century. But Corzo remained a strong competitor for a long while, winning five national titles between 1898 and 1918. He did poorly in a strong 1913 tournament in Havana — won by U.S. star Frank Marshall — but he did manage a beautiful win over Russian-born American star Charles Jaffe at the event.

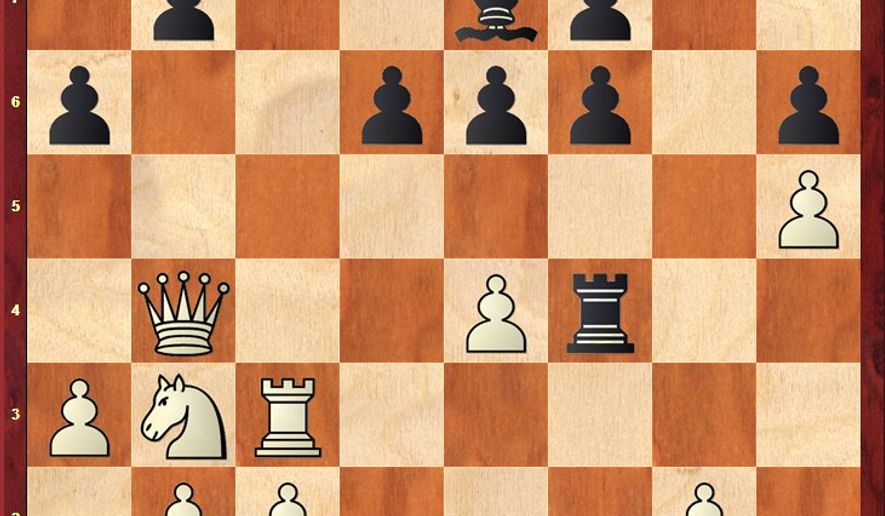

It’s an old-fashioned Giuoco Piano, with Black after 15. Bxe6 fxe6 16. h5 having two half-open files to offset his weaker pawn structure. But Jaffe’s 16…Rf4?! (Qc7 17. 0-0 Qf7 looks equal) just gives White a target, while 18. Rc1 d5?! prematurely opens up the game while Black is still developing his forces.

White clearly has the initiative when another Black mistake opens the floodgates: 24. Rh1 Qc6 25. b5! axb5 26. axb5 Qd6 (White invades on the queenside after 26…Qxb5 27. Rb1) 27. d4! g5? (a panicky response to White’s pressure; tougher was 27…exd4 28. cxd4 dxe4 29. Qxe4+ Kh8 30. Qe5 Qb4 31. Rc7, though White still has an edge) 28. hxg6+ Nxg6 29. Qxh6+!!, a killer shot.

It’s over on 29…Kxh6 30. Nf5+ Kg5 31. Nxd6 (recovering the queen and threatening 32. dxe5 Rff8 33. Rce1 Rg7 34. exd5 exd5 35. f4+ Kg4 36. e6 Rd8 37. f5 Rxd6 38. fxg6 and wins) 32. dxe5 Ra8?? (a mistake in a lost position, but Black goes down even in lines such as 32…Nf4+ 33. gxf4+ Kxf4+ 34. Kf2 Kxe5 35. Nxb7) 33. Nf7 mate.

—-

Capablanca was one of the first “grandmasters,” but the first official GM title awarded by FIDE to a Cuban player was earned by Silvino Garcia Martinez. Born in 1944, Garcia Martinez won the title in 1975, and has also served as president and president emeritus of the Cuban national chess federation for more than four decades.

One of his best wins was an upset of Smyslov at a 1974 tournament in Sochi, featuring a combination that remains controversial to this day. In a Sicilian Richter-Rauzer, Smyslov as Black consolidates and then plays for more in the game’s crucial sequence: 20. Rf3 Qg1!? (an excellent practical try for the win, but now Black’s queenside lacks defenders) 21. Nb4! (accepting the challenge) Nxb4 22. Qxb4 Ka8 (Rxg2!? 23. Nd4! Ka8 24. Rc3 is hard to meet; e.g., 24…b5? 25. Bxb5! Qxd1+ 26. Ka2 Bb7 27. Bc6! Bxc6 28. Rxc6 Ka7 29. Rc7+ Ka8 30. Qb7 mate) 23. Rc3 Rxf4 (see diagram) 24. Bxa6!? (one big question centers on whether 24. Na5!? wins here instead), a two-piece sacrifice that has inspired a messy debate.

After 24…Qxd1+ 25. Ka2, the computer finds 25…Qd5!!, exploiting an unexpected pin and throwing White’s whole idea into serious doubt. Now 26. exd5? Rxb4 27. axb4 Kb8! 28. Bf1 Rg5 consolidates for Black, and his two bishops should give him the edge in lines such as 29. dxe6 fxe6 30. Rh3 e5 31. Rh4 f5.

Black, understandably, can’t see through that thicket and goes down after 25…bxa6? 26. Qb6 (White is down a rook and a bishop, but his attack proves irresistible) Bb7 (Rf1 27. Na5 Qa1+ 28. Kb3) 27. Na5 Rb8 28. Nc6! Qg1 (a desperate measure to stop mate on a7, as 28…Bxc6 allows 29. Qxa6 mate) 29. Qxg1 Bxc6 30. Rxc6, and White’s material advantage and still-potent attack are decisive.

The finale: 31. Qe3 Rg4 32. Rc8+ Rb8 33. Qc3, and Black resigns facing 33…Rxc8 (Bd8 34. Qc6+ Ka7 35. Qd7+ Ka8 36. Qxd8) 34. Qxc8+ Ka7 35. Qc7+ Ka8 36. Qxe7 and wins.

Corzo-Jaffe, Havana, 1913

1. e4 e5 2. Nc3 Nc6 3. Bc4 Bc5 4. d3 Nf6 5. Bg5 h6 6. Bxf6 Qxf6 7. Nf3 d6 8. Nd5 Qd8 9. c3 O-O 10. b4 Bb6 11. a4 a6 12. Nxb6 cxb6 13. Qd2 Kh8 14. h4 Be6 15. Bxe6 fxe6 16. h5 Rf4 17. Qe3 Qc7 18. Rc1 d5 19. Nh4 Ne7 20. g3 Rf6 21. f3 Kh7 22. O-O Raf8 23. Kg2 Rg8 24. Rh1 Qc6 25. b5 axb5 26. axb5 Qd6 27. d4 g5 28. hxg6+ Nxg6 29. Qxh6+ Kxh6 30. Nf5+ Kg5 31. Nxd6 Rff8 32. dxe5 Ra8 33. Nf7 mate.

Garcia Martinez-Smyslov, Sochi, Russia, 1974

1. e4 c5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. d4 cxd4 4. Nxd4 Nf6 5. Nc3 d6 6. Bg5 Qb6 7. Nb3 e6 8. Qd2 Be7 9. h4 a6 10. h5 h6 11. Bxf6 gxf6 12. O-O-O Bd7 13. Rh3 O-O-O 14. Kb1 Kb8 15. Rd3 Rhg8 16. f4 Bc8 17. Qe1 Rg7 18. a3 Rdg8 19. Na2 Rg4 20. Rf3 Qg1 21. Nb4 Nxb4 22. Qxb4 Ka8 23. Rc3 Rxf4 24. Bxa6 Qxd1+ 25. Ka2 bxa6 26. Qb6 Bb7 27. Na5 Rb8 28. Nc6 Qg1 29. Qxg1 Bxc6 30. Rxc6 Rb7 31. Qe3 Rg4 32. Rc8+ Rb8 33. Qc3 Black resigns.

• David R. Sands can be reached at 202/636-3178 or by email at dsands@washingtontimes.com.

• David R. Sands can be reached at dsands@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.