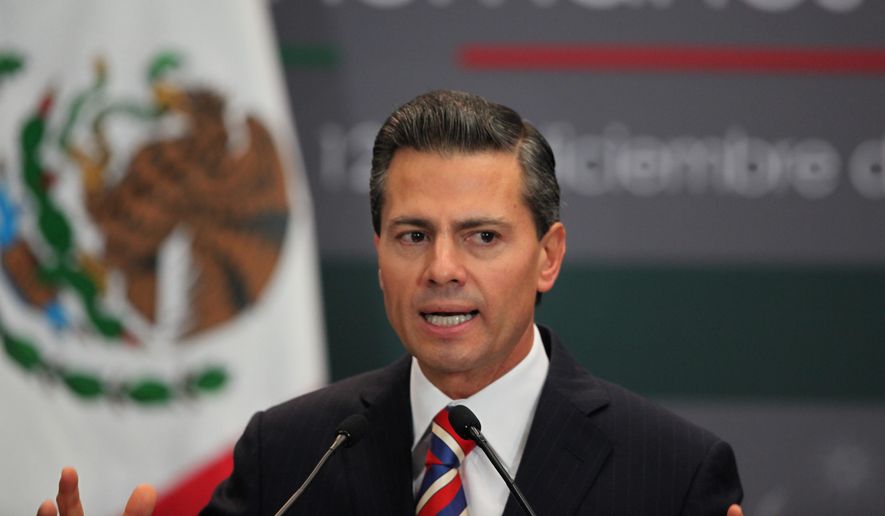

Mexico’s once-ultrapopular President Enrique Pena Nieto has become so scandal-plagued that questions are swirling in Washington on whether his government will be capable in 2015 of implementing such groundbreaking reforms as the U.S.-supported and politically delicate privatization of the nation’s oil sector.

Mr. Pena’s approval rating has dropped to unprecedented lows amid public outrage over the government’s failure to get to the bottom of a case involving the disappearance of 43 university students reportedly kidnapped and murdered with the help of police officers in southern Mexico in September.

But more recent accusations of crony capitalism, which saw Mr. Pena suddenly cancel a $4 billion high-speed rail project in November that had involved a major investment from China, may be more likely to damage his plan to raise his nation’s worldwide economic profile.

Mexican media has had a field day with reports that the sole bid for the project was made by a consortium that included the state-owned China Railway Construction Corporation and four Mexican companies linked to Mr. Pena himself. And analysts say the scandal has caused unease among foreign investors whose money will be needed to bring about the historic oil privatization.

“I think it causes investors to hesitate,” says Eric L. Olson, associate director of the Latin American Program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington.

“I’m sure companies are thinking that they have to make certain that there are guarantees and assurances that their investments will be protected from corruption and from other kinds of problems, like political mayhem,” he said. “They don’t want to walk into deals that may go bad, like the train deal did.”

Mr. Olson and others said Mr. Pena is capable of overcoming the current round of scandals. The oil privatization plan, which garnered international headlines when it passed Mexico’s Congress a year ago, along with Mexico’s relatively cheap labor and its access and proximity to the U.S. and Canadian consumer markets, are simply too attractive for foreign governments and companies to ignore.

But the Mexican president, who just nine months ago appeared on the cover of Time magazine accompanied by the headline “Saving Mexico,” faces an uphill battle, said Christopher Sabatini, the senior director of policy at the Americas Society and the Council of the Americas in New York.

“It’s difficult to see how this plays out,” he said, adding where there was once widespread hope that Mr. Pena may be a new face to Mexican politics, developments over the past few months have triggered a “real wellspring of public antipathy toward the Mexican political class” in general.

Mr. Pena swept into office in 2012 on a promise to crack down on the drug violence that has long damaged Mexico’s reputation and amid calls to boost his country’s trade relationships with Canada and the U.S. through an effort his staffers once called “NAFTA 2.0.”

But two years into his presidency, voters are increasingly worried that Mr. Pena’s Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) has reverted to the same old tricks that defined its control over the Mexican government for almost all of the 20th century.

Long accused by critics of crony capitalism and corruption, the PRI was ousted from power in 2000.

Mr. Pena effectively won the presidency in 2012 by convincing Mexican voters that he exemplified a 12-year reform of the PRI and that the party had shed its old system of top-down politics and patronage.

The catch, according to Mr. Sabatini, is that many Mexican voters now feel as if they were “seduced by the pretty boy and the new coat of paint on the PRI.”

“I think that’s why public reaction to the recent allegations of corruption has been so over the top,” he said, “because people are thinking, ’Hey, maybe we were just duped by a pretty face.’”

“There have been real reforms over the past two years, and I actually think Pena represents a different PRI from the decades past, but people still believe in that old PRI,” Mr. Sabatini added. “It’s as if they’re waiting to be betrayed by the old PRI.”

One of the most toxic accusations about the PRI during the years leading up to its 2000 loss of the Mexican presidency was that its leaders cut deals with drug cartels as a way to keep drug violence down in the nation.

While Mr. Pena and others in the party have long rejected such accusations, rumors swirled anew amid the Pena government’s failure to locate the 43 university students abducted in September in Iguala, a city in the southern state of Guerrero.

The case became an international scandal this fall when Mexican federal police accused the city’s mayor, Jose Luis Abarca Valezquez, and his wife, Maria de los Angeles Pineda Villa, of involvement in the kidnappings.

The two had fled Iguala following the disappearance of the students, but were arrested in November in Mexico City and charged with complicity in the case. Mexican federal authorities assert that Mr. Abarca actually ordered police in the city to arrest the students, mainly men in their 20s studying to be teachers.

The students disappeared while traveling in Iguala to attend a protest against poor government funding to the Raul Isidro Burgos Rural Teachers’ College, where they were studying.

News reports have cited Mexican officials as claiming that Mr. Abarca ordered the students to be arrested out of concern that their protest was going to disrupt a city event being hosted by his wife.

Several students are said to have been killed by police, and others are believed to have been handed over to a city gang to be executed.

While authorities have arrested dozens of people on accusations related to the kidnapping conspiracy, the overall case remains unsolved and continues to fuel public anger toward the government, sparking nationwide protests.

With the demonstrations still raging in November, corruption accusations arose around the bidding process connected to the Pena government’s plan to build a 130-mile rail line connecting Mexico City and the industrial city of Queretaro in central Mexico.

The Pena administration awarded a $4.3 billion contract to build a high-speed railway to China’s Railway Construction Corporation and four Mexican companies, including one known as “Grupo Higa,” but then, three days later, abruptly announced that the deal was being canceled and offered little explanation for the move.

The prominent website Aristegui Noticias, a news outlet run by prominent Mexican journalist Carmen Aristegui, then charged that the private home of Mr. Pena and his wife was built — and is currently still registered by — a subsidiary company belonging to Grupo Higa in 2012.

It followed that the $7 million home on a 15,220-sq.-ft. property in Mexico City’s most exclusive neighborhood was built by, and is actually owned by, a construction company that was later chosen by the Pena administration for the lucrative rail project.

Mr. Pena responded with a statement claiming that the president’s wife — former Mexican soap opera star Angelica Rivera — had signed a contract to buy the house almost a year before her husband became president and had made the purchase independently.

But the information, and the suggestion of cronyism in government contracting, prompted immediate public outrage.

It also triggered unease in China, whose foreign investment in Mexico had been jeopardized by the scandal.

China’s Railway Construction Corporation claimed that the cancellation of the bid was “due to domestic factors in Mexico and [is] unrelated to the Chinese side.”

But Chinese state media commentary was more critical.

“Many people’s first thought was: Is Mexico joking?” read a November commentary in the Communist Party-owned newspaper Global Times, according to The Associated Press.

“How can the tender for a project worth billions be pulled so carelessly?” the commentary read.

Mr. Olson told The Washington Times this week that the situation may have cast doubts in the minds of other foreign investors, and that it could be “a ticking time bomb” for the Pena administration.

“But I don’t think we’re there yet,” he said, adding that while the administration had a “relatively easy process” pushing through major reforms last year, it is now hitting some “rough terrain.”

“It’s an open question whether they can manage it or not,” he said.

• Guy Taylor can be reached at gtaylor@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.