The United Food and Commercial Workers Union is a heavyweight on the labor scene. It pays its president $350,000 a year. It’s holding its next executive board meeting in February at a swanky beachfront resort in Hollywood, Florida. And it just doled out nearly $8 million to influence the last election and lobby Washington.

But when it comes to standing by the obligation unions made to provide pensions to retirees, UFCW pleaded poverty in persuading Congress to let chronically underfunded union pension plans cut the benefits of workers, including those already retired.

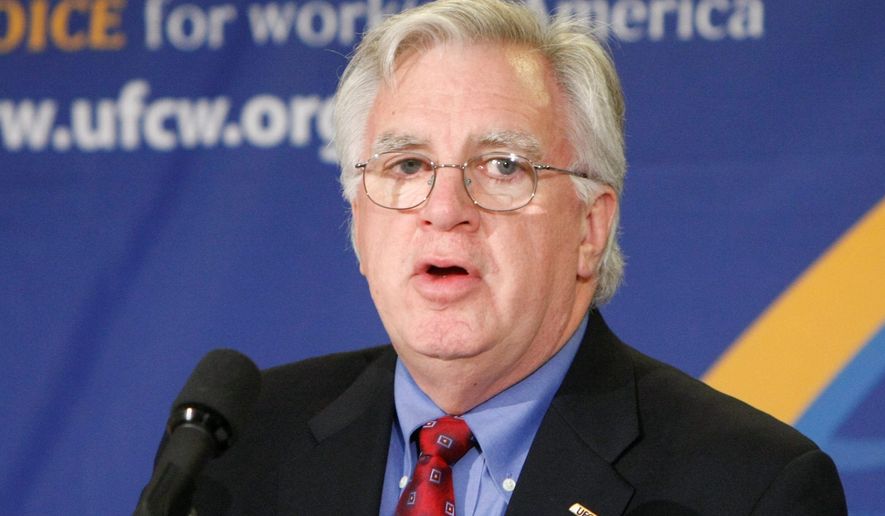

“Declining participation and factors like the Great Recession have created a new reality for Taft-Hartley multiemployer plans wherein many of them are substantially underfunded,” departing UFCW President Joseph T. Hansen wrote to the House Education and the Workforce Committee in a letter this month.

“The simple fact is that in order to save some of the most vulnerable pension plans trustees must be given the ability to slightly reduce benefits. This is the only realistic way to avoid insolvency and preserve as much of the promised pension benefits as possible,” the union boss wrote in a letter urging lawmakers to allow underfunded union pension plans to cut promised benefits.

Numerous other unions, many of them big spenders on the political front, also lobbied for the concession.

Congress obliged in a last-minute deal approved by lawmakers as they fled town for Christmas break. On Dec. 15, President Obama signed the Multiemployer Pension Reform Act of 2014 into law, empowering any multiemployer pension fund — commonly managed by unions — to cut benefits for workers and current retirees if the plan is 20 percent or more underfunded.

SEE ALSO: Obama golf game bumps Army couple’s wedding spot

In another words, Congress and the president let workers who spent decades toiling away to vest in retirement programs take the hit for union managers who failed to keep pensions fully funded.

In all, more than 10 million U.S. workers rely on multiemployer pension plans. About 1 million of those could get notices next year informing them that the pension benefits they were promised when they signed on to their jobs may be cut. Only those older than 75 get any relief.

The concession to union lobbying was a major reversal for Congress, which in the past steadfastly protected the pensions of workers who already had retired.

“The real point of contention is in the cutting of benefits in payment status, meaning benefits currently being paid to retirees. That’s a dramatic departure from long-standing legislation and practice that essentially says that benefits currently being paid cannot be reduced,” said Jean-Pierre Aubry, assistant director of state and local research at Boston College’s Center for Retirement Research.

Mr. Aubry said the new law will enable multiemployer plans to make deeper cuts to pensions than the 2006 Pension Protection Act allowed. “The new legislation allows for more dramatic cuts to the accrued benefits for current workers and, notably, allows for cuts to the benefits currently being paid to retirees,” he said.

The Multiemployer Pension Reform Act replaces many provisions of the previous law, creating an escape hatch for many underfunded pensions. The Labor Department’s list of critically underfunded multiemployer pensions shows that the vast majority belong to local unions.

When it came to lobbying, it was Big Labor that put its muscle into supporting the pension-cutting provisions, according to congressional correspondence reviewed by The Times.

Numerous unions, including the Service Employees International Union and the UFCW, sent letters to Congress urging lawmakers to pass the legislation. All were members of the 40-year-old National Coordinating Committee for Multiemployer Plans. In 2011, the coordinating committee assembled a Retirement Security Review Commission that authored a report designed to get quick congressional approval by asking for permission to trim benefits instead of relying on a government bailout.

That report, titled “Solutions Not Bailouts: A Comprehensive Plan from Business and Labor to Safeguard Multiemployer Retirement Security, Protect Taxpayers and Spur Economic Growth,” was published in 2013 and contained the architectural design and justification for the Multiemployer Pension Reform Act.

Rep. George Miller, California Democrat and longtime ally of big unions, and House Education and the Workforce Committee Chairman John Kline, Minnesota Republican and vocal critic of Big Labor, drafted the pension-cutting legislation this year.

Members of the National Coordinating Committee for Multiemployer Plans stepped up their involvement to seal the deal by sending letters to Congress.

Mr. Hansen’s Dec. 9 letter, which was one of his final acts before retiring as the union’s president, blamed hard economic times and declining union membership as reasons for the underfunded pensions.

But the country’s most famous senior lobby, AARP, said those explanations are oversimplifications of the truth.

AARP said Congress unnecessarily “carved a hole” into 40 years of federal law that protected retirees from having their pensions reduced retroactively and that affected retirees could have their benefits cut as much as 60 percent under the law.

It said it believed Congress had better options, such as allocating money to the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp. to cover union pensions in case of a default because many are years away from failure.

“These pensions aren’t in immediate danger of insolvency so there is no need to rush this drastic measure without considering alternatives such as scaling back on optional benefits in a plan or providing the PBGC with greater funds and the authority to intervene earlier,” AARP advocated in a blog post the day after Mr. Obama signed the bill. “Advocates also worry that this move by lawmakers might someday open the door to similar pension cuts in other plans.”

Officials for the UFCW did not respond to repeated requests for comment from The Washington Times.

But Randy G. DeFrehn, executive director off the National Coordinating Committee for Multiemployer Plans, said the legislative change was the only choice when many union pensions lost money after the dot-com bubble burst.

“After 2000, the markets didn’t start to perform very well. When the dot-com bubble burst, we started working with Congress on the PPA, which introduced some tighter constraints on plans and protected employers against unexpected contribution increases and excise taxes,” he said.

“That was helpful until we thought it was not going to work out in the long run. We were looking back at history, and there was not three consecutive years in the markets like there were from 2000 to 2002 since the 1940s. We believed the economists that this would be a once-in-a-lifetime experience, but then six years later we’re back in the soup in 2008 with the Great Recession.

“You’ve seen a lot of rhetoric saying this breaks with [the Employee Retirement Income Security Act’s] promises, but anytime a plan became insolvent those plans were reduced and they were reduced very deeply. They were cut to the PBGC levels, which is extremely low. What we were trying to do was find a way to preserve those benefits at a higher level because as part of the MPRA there are rules on how you can get relief, and they are consistent with what recommended by the commission.”

Further angering opponents of the new law is that many of the unions that sought help for underfunded pension funds continue to spend graciously on politics, lobbying and their own top executives.

Mr. Hansen’s last compensation of record in UFCW’s official records was more than $350,000 annually in 2013. His union spent $7.7 million on election campaigns plus $300,000 on lobbying this year, according to Federal Election Commission records and lobbying reports filed with the Senate.

The UFCW’s next executive board meeting will be at the oceanfront Diplomat Resort and Spa, where rooms run $300 to $550 a night and guests are treated to a four-star steakhouse, an 18-hole golf course and a 260-foot lagoon pool complete with two waterfalls and food and drink cabanas. The hotel confirmed that the meeting is set for the first week in February.

The optics aren’t lost on critics, and news media outlets that have chronicled large union spending on executives and high-powered lobbying firms even as their pension funds lingered near danger status.

According to the home page for the Workforce Fairness Institute, an advocacy group that researches union and collective bargaining issues, there is no shortage of “attempts by Washington politicians to pay back their union campaign donors through bailouts of various forms.”

In July 2012, The Wall Street Journal reported that unions spent more than $4 billion on political activity from 2005 to 2011, over $1 billion of which were contributions made through political action committees.

“The top political spender, counting both what is reported to the Labor Department and what is reported to the FEC, was the Service Employees International Union,” wrote the Journal. “Unlike most unions, the SEIU has seen its membership grow — to 1.9 million last year from 1.5 million in 2005. It reported spending $150 million on politics and lobbying in 2009 and 2010, up from $62 million in 2005 and 2006.”

That same month, Fox Business News reported a number of lavish spending sprees by unions in 2010 and 2011.

Fox Business News reported that the AFSCME spent more than $2 million on 10 conferences at resorts in Las Vegas, in Palm Harbor, Florida, and at the Tropicana in Atlantic City. The AFL-CIO spent 2.6 million in tax-free union funds on nine trips to the Flamingo Hotel and Golden Nugget in Las Vegas and the Westin Diplomat Resort in Hollywood, Florida. In 1998, the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers purchased a Learjet-60 valued at $13 million new or $5 million used.

The Diplomat Resort, where the UFCW is holding its next executive meeting, is union-owned. The United Association of Plumbers and Pipefitters of the U.S. and Canada reportedly bought the hotel in the late 1990s.

Mr. DeFrehn of the National Coordinating Committee for Multiemployer Plans said comparing the plight of union pension funds to the daily political expenditures of Big Labor is unfair.

He used the union event hosted at the Diplomat to make his case.

“Trustees have to be educated in this process, and they typically are very frugal in the dollars that they spend on education conferences,” he said. “The Diplomat is one we use quite often for our conference, and we started using it because it was owned by a pension plan. The profits that came to them flowed to the pension plan. It wasn’t an excessive thing.

“We made sure the rates are competitive, it wasn’t anything lavish, we were very careful about these kinds of things. We like to make sure the facilities themselves are union-represented so the people making a living there are participants in the plans we support. I think the idea that there are lavish meetings and getting high salaries is a way to throw mud.”

The pension law was enacted after the government-sponsored Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp., which protects pensioners when their plans fail, reported that its funding deficit soared $8.3 billion last year to a staggering $42.4 billion.

The law empowers the government to enter pension plans into “critical and declining status” if they are projected to become insolvent in the next 15 years. The government also may enter a plan into such status if it is projected to become insolvent in the next 20 years and the plan is less than 80 percent funded or the number of inactive to active participants exceeds a 2-1 ratio.

Entering such status enables the government to dramatically reduce paid benefits to plan participants even before the plans fail.

Congress created the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp. as part of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act to shield pensions. It currently monitors benefits for more than 41 million Americans in private-sector pension plans while paying benefits for nearly 1.5 million people participating in failed plans.

The Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp. has said it has assets to cover plans in trouble but lacks funds to cover plans that are scheduled to dry up in 15 to 20 years.

The Multiemployer Pension Reform Act was buried in the recent $1.1 trillion omnibus government budget and spending bill.

The process would work this way: A plan can enter “critical and declining status” with Treasury Department approval after its managers consult with the Labor Department and Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp. Plan participants can vote to override the government’s decision, but the Treasury Department can then veto the beneficiaries’ vote. Simply put, the government has final say.

There are limits to how much of the plan trustees can reduce and whose plans they can cut.

Retirees 80 or older or who receive disability pensions are exempt from the reduction. For retirees 75 to 79, reductions will be less than those younger than 75. For plans that cover 10,000 or more, pensioners can appoint representatives, and no reduced benefit can fall below 110 percent of PBGC’s benefit amount — what PBGC is supposed to pay to retirees should a plan collapse.

The law also requires that participants receive notice if their plan is underfunded and capable of reaching “critical and declining” status. The list is posted on the Labor Department’s website.

• Jeffrey Scott Shapiro can be reached at jshapiro@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.