OPINION:

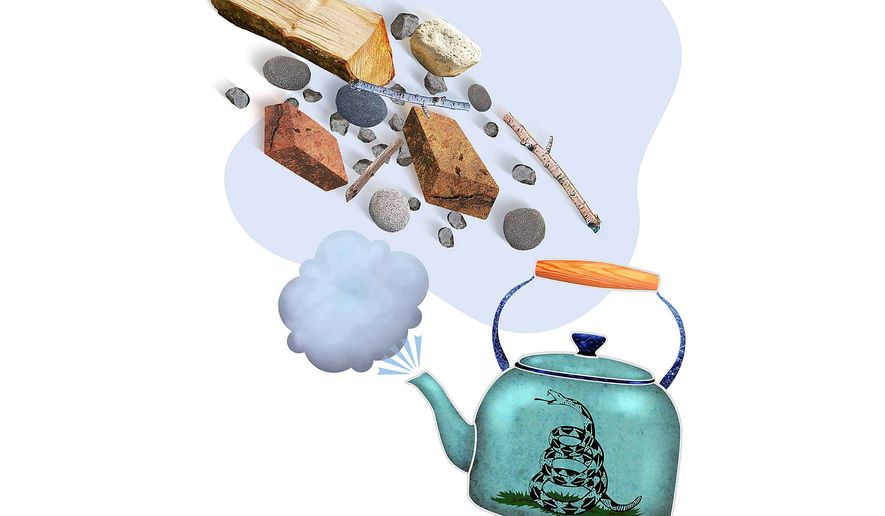

One of the curious aspects of the Tea Party’s emergence during the past four years is the extent to which the mainstream media have fostered the idea that this political phenomenon represents a kind of radicalism. Certainly, some politicians of the so-called Tea Party have tossed out ideas and expressions that have been silly and warped. Does that mean, though, that the Tea Party, as a broad political movement, is radical?

The answer is no. The Tea Party is a reactive movement, aimed at protecting the political mainstream from radical ideas, initiatives and policies of the left. Indeed, a review of American politics over, say, the last 50 years reveals that, to the extent America has been grappling with radicalism, it has been coming from the left. Then, as these ideas have gained traction through the agitations of the country’s liberal establishment, that establishment promptly labels those who resist as radicals.

By way of illustration, let’s go back to the year 1964 and assess the attitudes of Americans toward ideas that since that time have crept into the mainstream. Many of those ideas, viewed from this perspective, would have to be seen as radical.

Take, for example, homosexual marriage. Without getting into the question of whether government-sanctified same-sex marriage is a healthy or unhealthy cultural development, there can be no dispute that, 50 years ago, this idea was considered radical, almost unthinkable. As commentator Charles Krauthammer and others have pointed out, in the annals of man in society, there is a far greater tradition of polygamy than of same-sex marriage. Indeed, there is hardly any tradition of state-sanctified homosexual marriage at all in human history. Yet today in the West, polygamy is considered a radical idea (though there are signs of softening on that), while same-sex marriage is considered an entirely mainstream concept. Those who resist, standing on ground that was widely shared a few decades ago, are considered radical.

Further, those who are particularly intense in their support of same-sex marriage are incensed when their ideas are not allowed to trump freedom of religious conviction in America, which is a bedrock principle of our founding. Just in terms of dictionary definitions, that outlook would seem to be more radical than the view that religious freedom should be protected.

Or consider immigration policy. Fifty years ago, hardly anyone in America argued that the country should embrace a policy of open borders, which is essentially what the American policy has been the past three decades. It was widely understood throughout the American polity back then that serious nations must protect their borders and manage immigration through the rule of law. Today, on the other hand, it is an entirely mainstream idea that our borders don’t really matter, that the illegals already here must be made legal even absent any serious effort to stem the tide of illegal immigration (which has been down in recent years but will pick up again when the U.S. economy revives).

Another aspect of this is that liberals delight in admonishing conservatives and Republicans that they are on the losing side of history given the influx of immigrants who will never vote Republican so long as the party persists in its border-protection sensibility. Implicit in this is the assumption, which is largely indisputable, that these immigrants will vote their ethnicity, hoping to get more of their kind into the country so they can gain more and more political leverage. However, the mere hint that an American of Anglo-Saxon heritage, say, will vote his ethnicity, hoping to maintain the political leverage of his people, will immediately raise cries of racism. Thus does the liberal establishment manipulate the terms of debate to keep on the defensive those who resist ideas that, in 1964, were considered radical.

Going back 50 years on a number of other issues solidifies the point that most of the radicalism injected into the American mainstream has been coming from the left. Consider how people would have reacted back then, for example, to the idea of late-term abortion, once it were fully described. The consensus reaction would have been shock and dismay; now it is defended vociferously by many on the left. Other examples: the idea of sending American soldiers into harm’s way for purely humanitarian purposes, divorced entirely from U.S. national interest; the usurpation of executive authority in the federal government; the assault on religious expression in the public sphere, such as Christmas displays; the degradation of popular culture that invades the consciousness of our young people.

A half-century ago, there was a strong national consensus on all these things: Humanitarian interventionism was a bad thing; executive power must be checked; mild displays of our religious heritage didn’t hurt anybody; our children should be protected from cultural filth such as today’s rap lyrics. To think otherwise was considered radical.

Now all that radicalism has entered the mainstream, compliments of the American left — the same left that now assaults the Tea Party as a bunch of radicals seeking to infect the American mainstream. That’s a display of polemical gymnastics that is stunning when you think about it. Viewing it with clarity requires stepping back from the mainstream discourse and looking at the matter in some historical context.

Robert W. Merry, political editor of The National Interest, is the author of books on American history and foreign policy.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.