OPINION:

President Obama wasn’t kidding about acting on his own if Congress won’t go along with his plans to “fundamentally transform” the country that elected him president. Sometimes he tries his phone, then if Congress blocks his agenda, his pen, but more and more often he’s simply acted without consulting or even informing Congress. In some cases, he’s even actively sought to keep Congress in the dark about new programs he’s started without even submitting them to Congress for approval.

This year, Congress has even learned about administration initiatives not from the White House, or the agencies implementing them, but from the press or their own constituents.

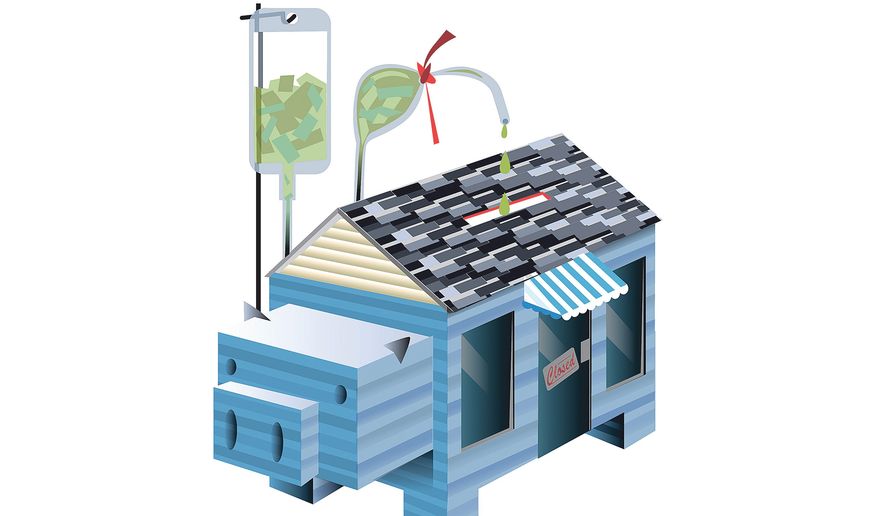

Thus it was with Operation Choke Point, an interdepartmental program designed to cripple or eliminate completely legal businesses just because the administration doesn’t like them. The idea for the program apparently came from a zealous and perhaps overly ambitious prosecutor in the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Philadelphia, who suggested to his superiors that the government could persuade banks to call loans, refuse to make loans or otherwise do business with certain industries, forcing many enterprises to close.

The resulting operation involves the Department of Justice, the FBI, the newly formed Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and, most importantly, the bank regulators at the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). The folks at the FDIC audit banks large and small and can send bankers searching for their Maalox simply by raising an eyebrow.

Complicated in its details, the plan is conceptually fairly simple. Internet and credit card purchases require the assistance of banks and third-party processors to clear payments and to stay in business. Large and small businesses also need and operate on lines of credit from lenders with whom they may have been doing business for years or even decades.

The government decided to inform banks and processors that some business sectors were higher risk than others. Businesses operating within these sectors might be more prone to defrauding their customers or breaking other laws, and a bank providing such “high-risk” businesses services could be viewed by bank regulators and federal law enforcement officials as accomplices in whatever laws the high-risk enterprise might break. A financial institution providing services to such a business might have to be more carefully and extensively audited than other banks to make sure it is diligently checking on its high-risk customers to make sure nothing is amiss.

In meetings with bank officials, the feds made it clear that the bankers have every right to provide services to such businesses, but warned them that doing so might put them at risk, too, and could almost certainly trigger more extensive audits than would be required of banks that don’t service such customers. Bankers depend for their very survival on those who regulate them and know a threat when they hear one. Many decided it would be wiser to quietly get rid of customers in such high-risk businesses.

As a result, customers of long-standing around the country had their lines of credit called and their accounts closed. The affected businesses were never officially told why, because the government made it clear to the banks that they would face criminal charges if they talked. Even as the feds were briefing bankers on the program and their need to protect themselves by choking off high-risk businesses, the Justice Department was refusing to brief Congress on what was going on.

Although the administration claims it is mainly after the so-called “payday” lending industry, at one point officials provided a much more extensive list of objectionable “high-risk” business types to bankers. The list included gun dealers and manufacturers as well as firearms retailers, retailers advertising consumer products on television, gambling, products whose producers offer “lifetime” guarantees, home-based charities, those who distribute or sell tobacco products and third-party payment processors, among others.

Before the existence of the program became public, a number of firearms dealers and distributors complained that their banks had cut them off as part of some government effort to put them out of business. The first wave of complaints was dismissed as the sort of thing one might hear from a conspiracy buff or a paranoid. Congressional aides assumed the complaining firms had other, probably legitimate problems, which cost them their credit and banking relationships. Similar complaints from businesses in other industries were dismissed for the same reasons.

It is now clear, however, that these businesses have been targeted for extinction and that men and women who have broken no laws are suffering positive harm for the simple reason that the Obama administration wishes they’d take up a different line of work. Congress is investigating, the administration is stonewalling, and Americans are suffering at the hands of bureaucrats after them because they just don’t like them.

That, in today’s America, is what passes for the rule of law.

David A. Keene is opinion editor of The Washington Times.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.