Forget what most experts are saying about the jobs picture — if you work in America in the private sector, you will earn less during your career than previous generations, you will have fewer benefits, and you will spend long periods unemployed and trying to reinvent yourself.

As massive layoffs announced recently by Cisco and Microsoft illustrate, even choice jobs in America’s private sector can disappear. If your job is not “outsourced” to rising nations where grateful employees work cheerfully for less, machines are coming soon to take it away.

Though politicians in both parties brag otherwise, the truth is the employment situation is dire and only getting worse.

Each year in August, the Commerce Department updates statistics concerning the employment picture that show trends in the number, wages, and total compensation of employees, converting figures for part-time workers to “full-time equivalents.”

Unlike information presented in the Employment Situation Summary presented monthly by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, annual data from the Commerce Department break down estimates of full-time equivalent employees between the public and private sectors, as well as by industry.

Between 1998 and 2008, the recent peak year for employment in America, full-time equivalent employees rose from 118.2 million to 128.9 million — a cumulative increase of 9.1 percent.

SEE ALSO: Unemployment rose to 6.2 percent in July; 209K jobs added

Since then, despite massive deficit spending by our government and despite extraordinary intervention in capital markets by central banks, full-time equivalent employment dropped 1.5 percent from 2008 to 127.0 million employees currently.

The employment picture is even worse when you look below the surface.

Since 2008, employment in government, health care, education and legal services (a broader estimate of public and quasi-public sector employment) rose 2.9 percent from 39.2 million to 40.3 million. Meanwhile, employment in the core of the private sector that is most exposed to threats from global and technological competition dropped 3.4 percent from 89.7 million to 86.7 million.

Measured in 2013 dollars, wages per full-time equivalent employee in the core private sector increased 9.4 percent from $50,220 in 1998 to $54,917 in 2008, then rose only 2.6 percent to 56,335 in 2013, even as private sector employment levels dropped.

Incomes under pressure

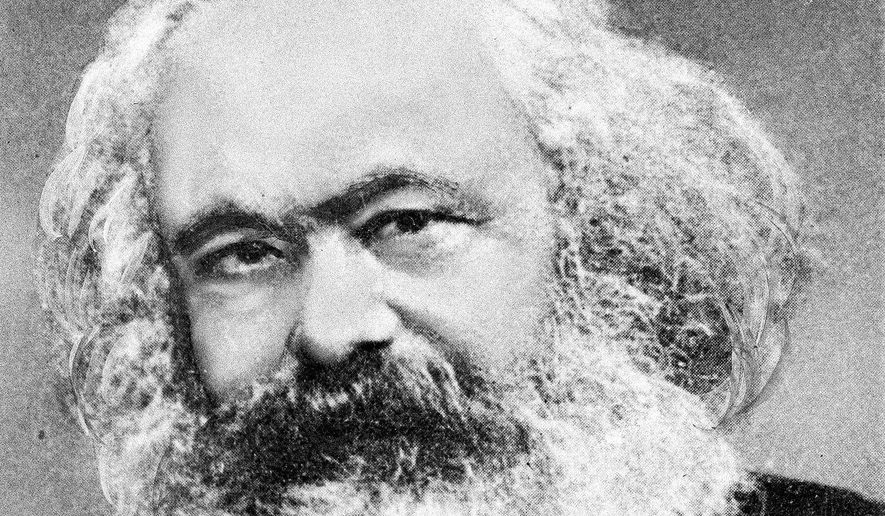

Karl Marx was absolutely correct when he noted in 1844: “If the supply greatly exceeds the demand, then one section of the workers sinks into beggary or starvation. The essence of the worker is, therefore, reduced to the same condition as the existence of any other commodity. The worker has become a commodity, and he is lucky if he can find a buyer.”

Estimates prepared by the United Nations demonstrate there is a massive global labor glut that will continue hurting high-cost workers in America and the balance of the developed world more than in any other geographic region.

In 1998, the American non-agricultural workforce was 140.0 million persons out of 446.2 million in the developed world and 1.48 billion worldwide.

By 2008, the non-agricultural workforce grew 11.2 percent in America to 155.7 million persons; 10.0 percent in the developed world to 490.9 million persons; and 34.3 percent outside the developed world. Overall, growth in the global non-agricultural workforce was 27.0 percent to 1.88 billion persons.

In 2013, the non-agricultural workforce increased by 2.4 percent in America to 159.4 million persons; by 2.3 percent in the developed world to 502.3 million persons; by 13.7 percent outside the developed world to 1.58 billion persons; and by 10.7 percent worldwide to nearly 2.1 billion persons.

Absent a global population scourge (and we certainly hope the Ebola virus will not become one), jobs and incomes are likely to keep flowing outside the developed world, where workers will accept far lower compensation than we demand in America.

On this point, Karl Marx is right.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.