NEWSMAKER INTERVIEW:

The government’s top watchdog for Afghan reconstruction says the State Department’s failure to provide guidance over the use of billions of dollars in U.S. funds for rebuilding projects is exacerbating problems with rampant corruption ahead of the much-anticipated U.S. troop pullout.

In an exclusive interview with The Washington Times, Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction John F. Sopko raised red flags about the State Department’s shortcomings before he testifies to Congress on Thursday about the wasteful government spending in Afghanistan.

Mr. Sopko said he will brief lawmakers on issues related to the reconstruction efforts of the U.S. Agency For International Development, which administers civilian aid.

Afghanistan is approaching a pivotal point in its nascent democracy. Remaining U.S. troops are preparing to exit the country, and a new president will soon have to grapple with an odd mixture of uncertain security plans, piecemeal conversations with the violent Taliban and haphazard reconstruction projects peppered with corrupt opportunists.

The inspector general warned that the confluence of circumstances is a harbinger of emerging problems and that Afghanistan — and the State Department — are poisoning the well from which reconstruction money is drawn.

“They’re not living up to their requirements that have been imposed by the international community on fighting crime, corruption — all that,” Mr. Sopko said. “We’ve continued the funding. We’ve waived our internal controls. We really have not held their feet to the fire.”

The State Department did not respond to requests for comment on the charges.

Feet to the fire

Mr. Sopko, who became inspector general in July 2012, said he took the job with confidence after he asked State Department officials to define for him what the “test on corruption” should be. After being appointed by President Obama, he said, he was told he should hold “the State Department’s feet to the fire” and ensure that Afghanistan meets all requirements of international agreements designed to help the country achieve key development and governance goals.

The framework commits the United States to providing $16 billion to the Afghan government through next year and to sustaining financial support to the country through 2017.

But ensuring that those billions of dollars are going toward reconstruction efforts and not corrupt politicians has proved difficult, he said. The Afghan government has been having difficulty combating corruption and increasing accountability in part because the State Department never finalized a draft 2010 U.S. anti-corruption strategy for the country.

“We never came up with the benchmarks — specific benchmarks that the Afghans promised to meet on corruption, women’s issues, rule of law, etc. — never established them,” Mr. Sopko said. “So we never held the Afghans to them.”

The latest example

Proof of Mr. Sopko’s claims came in the form of a letter Wednesday to Secretary of State John F. Kerry. Mr. Sopko delivered the letter a day before his public square off with Donald Sampler, assistant to the administrator in the office of Afghanistan and Pakistan affairs for the U.S. Agency for International Development, in front of the House Oversight and Government Reform subcommittee on national security.

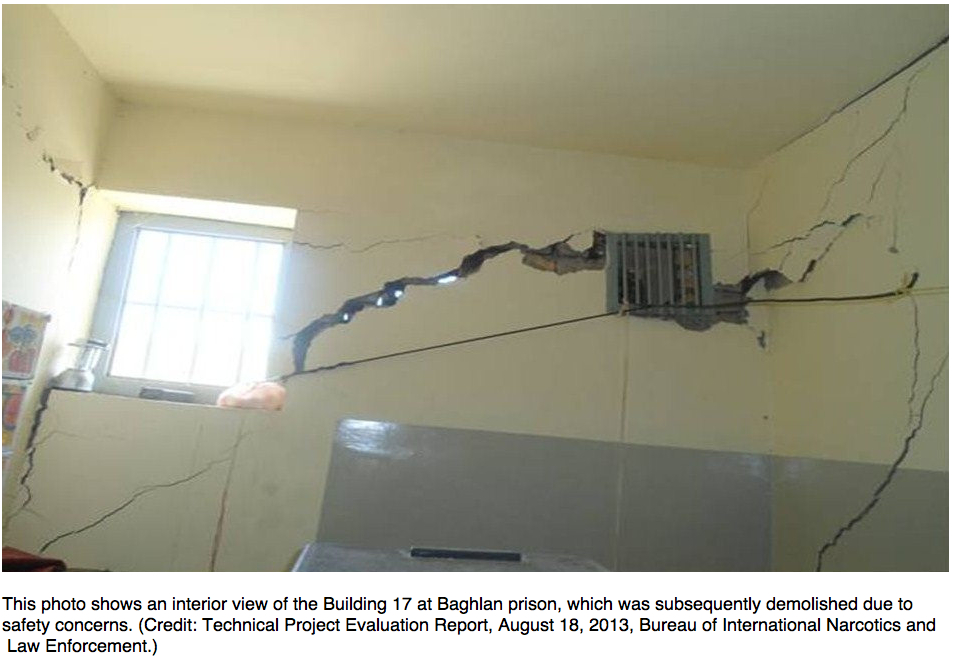

In the letter, Mr. Sopko says he has uncovered an issue of reconstruction gone awry in eastern Afghanistan. A prison in Baghlan, he said, is riddled with design and construction defects because the State Department hired an Afghan firm to build it and that Afghan firm essentially failed to comply with international building code requirements for masonry structures.

The contract for the 495-inmate prison, begun in 2010, was valued at $8.8 million but eventually increased to about $11.3 million after a series of contract modifications, Mr. Sopko said.

State Department officials briefed on the conclusions did not dispute the oversight organization’s assertion that the contractor built the prison facility using a faulty construction method, according to the letter.

Diminishing oversight

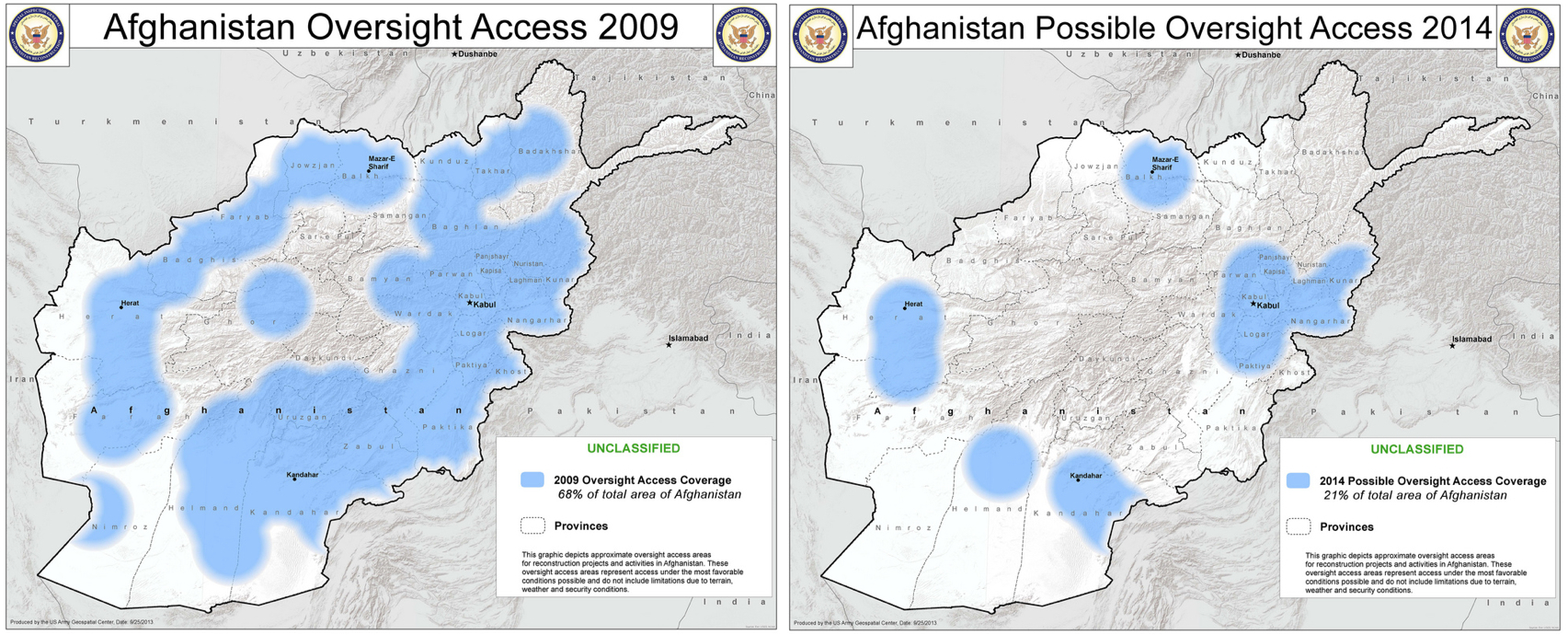

Complicating efforts to rein in waste, Mr. Sopko said, is that his ability to access parts of Afghanistan has been diminished. In 2009, the inspector general’s office had access to about 68 percent of Afghanistan. Last year, his reach shrunk to about 45 percent of the country.

Mr. Sopko anticipates having his oversight reach reduced to about 21 percent of the country this year, according to a map provided to The Washington Times. That means more than 70 reconstruction projects likely fall outside the range of the oversight organization.

In addition to oversight issues, the inspector general said, a multinational military formation known as the Combined Security Transition Command-Afghanistan is having difficulty keeping corruption out of the armed forces acquisition process. The organization is working to establish a set of safeguards to fence out crooked contractors, he said.

“And I know they’ve got a bunch of ideas on how to do it, but they need to get out there,” he said. “They need to design their own system to deal with it.”

Col. Jane Crichton, a spokeswoman for the NATO-led International Security Assistance Force, said the Combined Security Transition Command-Afghanistan is working to increase the amount of funding that is provided directly to Afghans for their security as the country develops the abilities to manage and execute resources.

She said the military formation asked Defense Department Inspector General Jon T. Rymer to “conduct a comprehensive assessment of how funds are accounted for within the Afghan financial system.”

For most of March, Mr. Rymer had a team in Afghanistan conducting an independent audit in three Afghan ministries, Col. Crichton said. The result of that audit will be available within the next few months, she said.

Uncertain future

The immediate future remains uncertain. With the presidential election process beginning in Afghanistan on Saturday, the role NATO will play in the country after December is being used as a political point among politicians.

Afghan President Hamid Karzai has made clear he will not sign a security agreement that establishes a long-term framework for the presence of U.S. military troops in Afghanistan past the end of the year. Leading candidates, however, have said they would sign that security agreement.

Michael O’Hanlon, a senior Brookings Institution fellow specializing in national security and foreign policy issues, said high-profile corruption scandals could cease under a new president. In Kabul, the main bank that paid salaries of security forces nearly collapsed after $1 billion in U.S. funds were squandered.

Mr. O’Hanlon predicted that the downsizing of the international presence should help reduce the funds for corruption. He also said the gradual strengthening of the Afghan state will help curb corruption if accountability is in place. Establishing benchmarks to hold the U.S. and Afghan governments accountable for those funds would be a step in the right direction, Mr. O’Hanlon said.

“Benchmarks, in a loose sense, are useful,” he said. “Benchmarks in an arbitrary or rigid sense can be useless or even counterproductive. But I do support a cohesive written strategy.”

• Maggie Ybarra can be reached at mybarra@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.