The Supreme Court on Thursday upheld the heart of President Obama’s health care law, ruling the federal government can compel Americans to buy health insurance, and striking a new balance for the scope of federal authority in the 21st century.

The ruling lets Mr. Obama continue to push the law ahead of its full implementation in 2014 and will likely amp up pressure on a number of states who had been awaiting a court decision before plowing ahead with state requirements.

The complex 5-4 decision is a major legal boost to Mr. Obama just months before he faces voters in a battle for re-election, and it complicates matters for Republicans on Capitol Hill, who had turned to the courts after their repeated efforts to repeal the law fell short in Congress.

Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr., who wrote the controlling opinion, attempted a delicate balancing act: He said the Commerce and Necessary and Proper clauses of the Constitution cannot be bent to compel Americans to buy insurance, but said it is allowed under Congress’s tax and spending powers, which are broader, but are subject to the checks of the political system.

“The Affordable Care Act’s requirement that certain individuals pay a financial penalty for not obtaining health insurance may reasonably be characterized as a tax. Because the Constitution permits such a tax, it is not our role to forbid it, or to pass upon its wisdom or fairness,” he wrote.

The court’s four Democratic-appointed justices all joined the Roberts ruling but wrote separately to say they would have allowed the individual mandate under the Commerce Clause, too.

Four justices dissented, saying in an opinion written by Justice Antonin Scalia that the court has granted nearly unlimited authority to Congress to control Americans’ lives.

“Whatever may be the conceptual limits upon the Commerce Clause and upon the power to tax and spend, they cannot be such as will enable the Federal Government to regulate all private conduct and to compel the states to function as administrators of federal programs,” Justice Scalia wrote.

They said they would have struck down not only the individual mandate but the rest of the law as well, arguing that the other provisions could not have stood without the compulsion of forcing Americans to buy insurance.

Chief Justice Roberts’ ruling also upheld the law’s massive expansion of Medicaid, but said states cannot be compelled to expand their own programs through the threat of removing federal funding altogether. Instead, states have the choice of expanding and collecting new federal money, or staying at current coverage and federal funding levels.

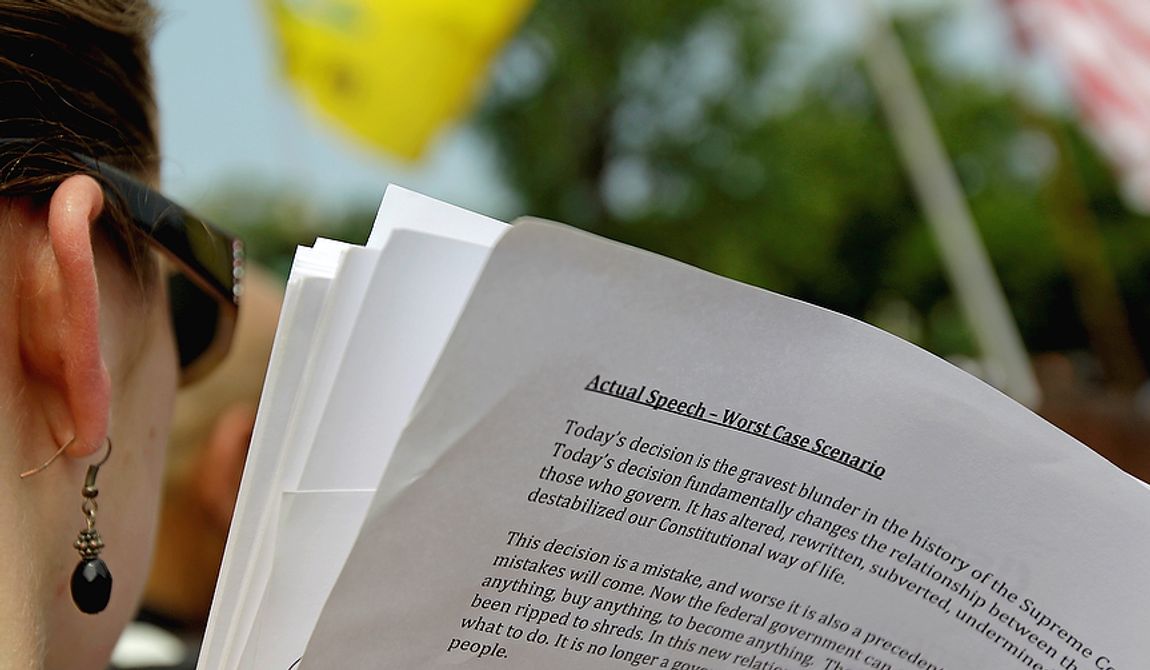

The political fight was already ramping up Thursday morning, with Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell saying the court has stripped away the pretense and exposed the tax increases in the law.

“The Supreme Court has spoken. This law is a tax. The bill was sold to the American people on a deception,” Mr. McConnell said, adding that the GOP will continue to pushing to ax the law.

“The court’s ruling doesn’t mark the end of the debate. It marks a fresh start on the road to repeal,” he said.

And Majority leader Eric Cantor said the House will vote to repeal the health care law next month, delivering on GOP promises to try to repeal the rest of the law even if the court upheld it.

“The Court’s decision brings into focus the choice the American people have about the direction of our country,” he said. “The president and his party believe in massive government intrusions that increase costs and take decisions away from patients.”

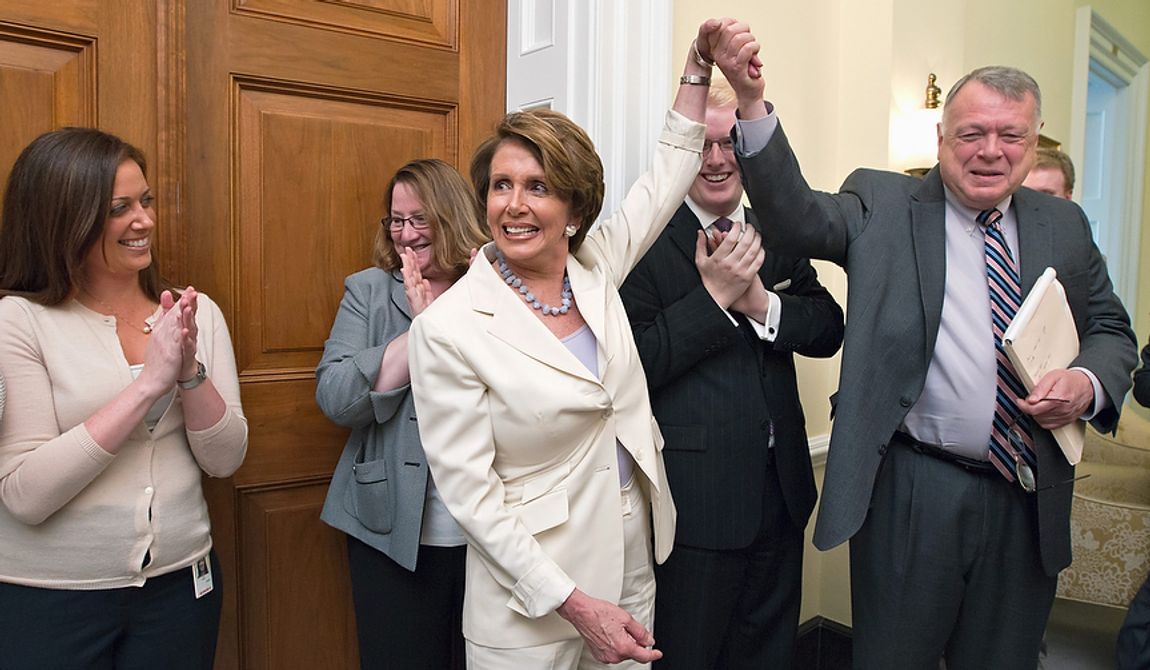

But Democrats said the ruling will give them time to implement the law and sell its benefits to the public, even as they plan tweaks.

“No one thinks this law is perfect,” said Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, Nevada Democrat. “But Democrats have proven we’re willing to work with Republicans to improve the problems that exist in this law or any other law.”

All eyes have been on the court ever since the justices announced they would hear major constitutional challenges against the Affordable Care Act.

The individual mandate to buy insurance or pay a fine was at the heart of the struggle, marking the first time the federal government had tried to require all Americans to buy a particular good or service.

While opponents said it violated individual freedom, the administration said since everyone consumes health care at some point, government can control when they begin to pay for it.

The justices held a marathon three-day series of oral arguments in March and then retreated behind closed doors to deliberate and write their opinions.

The conflict gave the Supreme Court a chance to try to spell out the federal government’s relationship with states and individuals more clearly than ever before, indicating where the government’s powers to tax, to regulate interstate commerce and to enact “necessary and proper” laws began and ended.

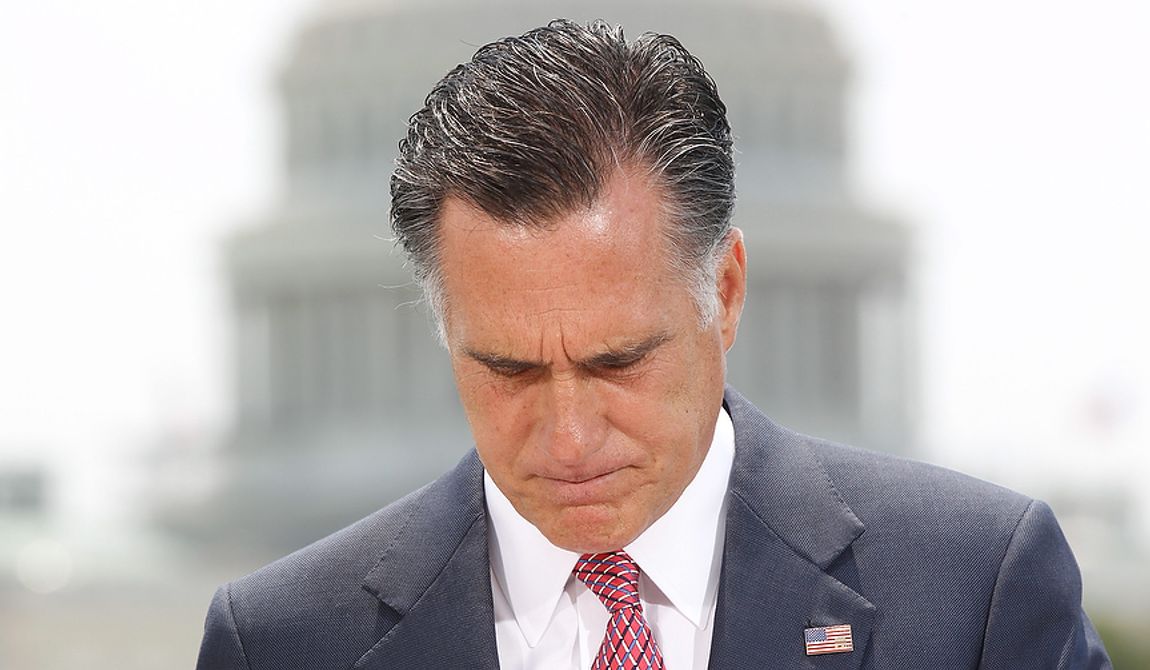

Voters have been sharply polarized over the law since the beginning, and the court’s ruling is likely to dominate the presidential campaign as Mr. Obama tries to fend off presumptive Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney, who himself signed a pioneering health law as governor of Massachusetts.

The Supreme Court’s decision comes after more than two years of courtroom battles over the 2010 law.

As soon as Mr. Obama signed the law, Virginia Attorney General Ken Cuccinelli filed a lawsuit challenging the individual mandate, and in the ensuing year more than half of the states united to challenge the mandate and the bill’s massive expansion of Medicaid, which is the federal-state health program for the poor.

The court challenges have left the law in limbo for many.

Some states started working on setting up their mandatory insurance exchanges. But other states, especially those run by Republicans, decided to sit back and wait for the ruling before they made any moves.

Throughout, the Obama administration touted the immediate benefits of the law: more federal support for prescription drugs for some Medicare beneficiaries; children up to 26 years of age who are able to stay on their parents’ health policies; and an end to limits on coverage, such as preexisting conditions.

But the health care deliberations also helped spawn the tea party political movement that powered Republicans to victories in the 2010 elections and gave them control of the House — which has since voted dozens of times to repeal all or part of the law.

Those efforts have almost always fallen short, but the administration has accepted some changes.

Mr. Obama has signed bills that repealed an onerous business reporting requirement and two other bills that have cut the levels of health exchange subsidy overpayments that would have been allowed. In those last two cases the changes were made so the money could be used for other government priorities.

And the administration on its own said it will not move forward with the CLASS Act, a part of the bill championed by the late Sen. Edward M. Kennedy that was designed to cover long-term care, but which all sides now agree is fiscally unsustainable as written.

Throughout, both sides knew a final ruling from the court would be decisive.

Major insurers such as United Healthcare and Aetna had already announced they would keep some of the law’s most popular provisions even if it was overturned, including the mandate to include children up to age 26 on their parents’ policies and fully cover some preventative services without charging a co-pay.

The Supreme Court had its pick from a number of cases that wound their way through the justice system, but chose to hear one decided by the 11th Circuit — the only appeals court to throw out the individual mandate but uphold the rest of the law.

During oral arguments the justices grappled with a number of major constitutional issues, including whether requiring Americans to buy health care violates their liberty, how much of the law could function without the individual mandate and whether states can opt out of the Medicaid expansion without losing out on new federal dollars.

The question about the individual mandate garnered the most public attention, widely seen as a referendum on how much influence the federal government may assert over Americans’ purchasing decisions.

Many court-watchers said post-ruling that the court appeared more likely to strike down the mandate after Justice Anthony M. Kennedy and Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. — expected to be swing votes — were especially tough on Solicitor General Donald Verrilli, who argued for the administration.

The justices seemed to agree that striking down the mandate would dramatically alter the rest of the law, but disagreed on which route to take. The Republican-appointed justices appeared to lean toward scrapping the whole thing while the Democrat-appointed justices said that’s a decision for Congress to make.

Each sides faced the challenge of describing limits to the power they sought.

When the justices challenged him to name something the government couldn’t do if it could require Americans to buy health coverage, Mr. Verrilli said that health insurance is unique because if anyone can’t pay for their own health care, those costs are shifted onto other people.

Meanwhile, attorney Paul Clement, who argued for the National Federation of Independent Businesses and 26 states opposing the law, struggled to explain why the states couldn’t reject all sort of rules attached to federal programs if they could reject the Medicaid expansion.

• Paige Winfield Cunningham can be reached at pcunningham@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.