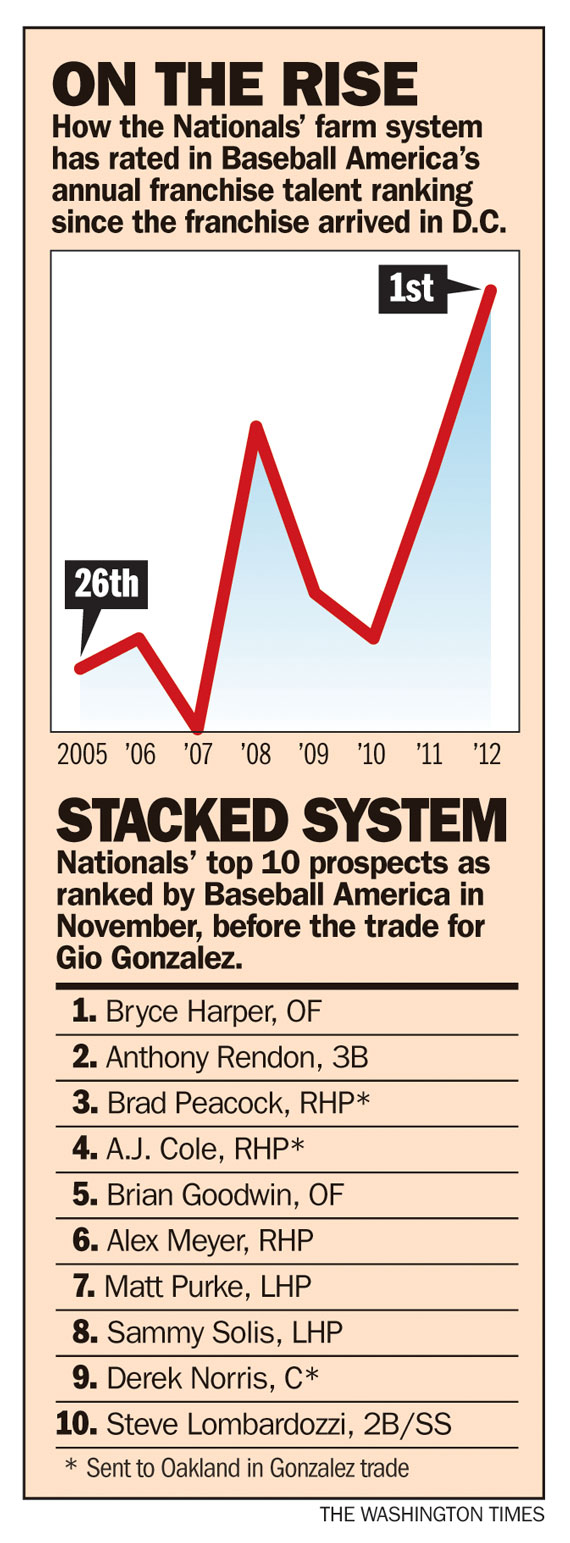

The first email arrived to the entire baseball operations staff around 3 p.m. on Feb 1. The surprise was in the sender: Washington Nationals general manager Mike Rizzo, who rarely corresponds via email. The pride was in the topic: “Congratulations.” Baseball America, one of the industry’s pre-eminent publications, had ranked the Nationals’ farm system No. 1, and Rizzo felt it apt to express his thoughts to everyone who’d had a part in achieving that benchmark.

The second email came in shortly thereafter. This one was from principal owner Mark Lerner and it carried the same tone of gratitude and satisfaction. It also reflected perhaps the most impressive part of the recent rankings: When the publication’s 2007 rankings came out in February of that year, the Nationals were on the other end, No. 30. They were owners of the worst farm system with a “best prospects list” that some would say was ineptly titled. Esmailyn Gonzalez, who turned out to be Carlos Alvarez and four years older than he’d said, was their prized international acquisition.

“We knew better than anybody the condition that we purchased this team,” Lerner said. “To get from the Dead Sea — below sea level — to going up Mount Everest, it’s a long haul. Doing it in just five years, patting ourselves on the back, it’s pretty phenomenal.”

The ranking will change. The Nationals traded four of their best prospects to Oakland in December for left-hander Gio Gonzalez, and Baseball America’s executive editor, Jim Callis, said the organization will drop into the No. 5-10 range. ESPN.com’s Keith Law ranked them much lower, No. 21, because of what he said was a lack of depth. Before the trade, he concedes, they’d likely have been in the top 10.

But through an aggressive approach to the draft, where they spent more than $33 million on their top 12 picks the past three years, and a front-office roster heavy with scouting backgrounds and on-board with the organization’s vision, the Nationals’ find themselves miles from their starting point — just like they planned.

’It’s impossible to rush it’

When the Lerner family assumed ownership of the Nationals on May 3, 2006, it did so with no illusions.

“The team was No. 30 because there were only 30 teams,” said former team president Stan Kasten. “It would have been lower. No one was to blame. The team was being propped up for sale … and the farm system was allowed to, let’s say, wane. We knew that nothing good was going to happen — because it never does in baseball — until you had the proper scouting and player development system in place.”

They made that clear in their introductory news conference despite the knowledge that it would come with several painful years. Pushing through the Esmailyn Gonzalez scandal; failing to sign 2008 top pick Aaron Crow; losing more than 100 games in back-to-back years — it all was painful.

“Patience is the toughest thing to sell,” Rizzo said. “But the knowledgeable owners and the knowledgeable fans understand that it’s impossible to rush it. You can’t buy championships. You can buy short-term success.”

“Patience is the toughest thing to sell,” Rizzo said. “But the knowledgeable owners and the knowledgeable fans understand that it’s impossible to rush it. You can’t buy championships. You can buy short-term success.”

Thus began what became known as “The Plan.” Rizzo, a scout at his core, was the Lerners’ first hire as an assistant to then-GM Jim Bowden. The transformation of the scouting and player development department from that point was slow but dramatic.

“[Before the change in ownership] we only had nine scouts running around seeing players,” said former scouting director Dana Brown, now an assistant GM with the Blue Jays. “To put that in perspective, [in Toronto] we have almost 52 scouts.”

Brown recalled the 2003 draft, when he watched Matt Kemp go off the board in the sixth round with no idea who the future NL MVP candidate was. The Montreal Expos (who moved to D.C. and became the Nationals for the 2005 season) hadn’t scouted him. But the lack of manpower was just one issue. Under MLB rule, the team wasn’t allowed pay draft picks over the recommended value and Brown was powerless as they passed by top players, knowing they couldn’t afford them. That changed with the Lerners.

“When we get to the [Stephen] Strasburgs and the [Bryce] Harpers and [Anthony] Rendons and [Matt] Purkes of the world, honestly, we didn’t have reservations,” Lerner said. “Yes, it was expensive. Yes, it’s hard to sign that check once in a while. But at the end of the day, the bottom line was we were lucky to be in position to get these quality players.”

The staff also continued to evolve. Rizzo was the scouting director who brought Arizona from the No. 29 ranking in 2001 to the No. 1 spot in 2006 and much of his staff joined him in Washington, including scouting director Kris Kline. Kasten, who’d been instrumental in building the Atlanta Braves into a dynasty through a similar progression with Roy Clark, also was instrumental. Clark joined the Nationals in 2009. A scouting background became prevalent. Even director of player development Doug Harris came to Washington after 14 years as a scout.

And it wasn’t just the top-end executives. The team’s 2011 media guide listed 28 scouts — nearly triple what it had been before the Lerners stepped in.

In the wake of the accolades, Kline credited the development side; Harris pointed to the recent drafts rich in talent. They agreed on two things: They’ve been given the autonomy to do their jobs without interference and everyone speaks the same language when evaluating players.

“I think there are a lot of teams whose farm system is very separate from the scouting portion,” said Kline, who speaks regularly with Harris. “It’s like a marriage. It’s still a work in progress, but we’re so much closer now to having one mindset — and when you can do that, it’s almost impossible to fail.”

Attacking the draft

When Rizzo interviewed for the general manager’s job following Bowden’s resignation in 2009, he spent much of the session discussing a draft strategy. A new collective bargaining agreement was coming in 2012, and there would no doubt be changes to the structure. They had three drafts to use the old system to accelerate their progress.

“I never understood why more teams weren’t more aggressive,” Callis said of the previous draft setup. “It was a tremendous system that was easily exploitable if you were willing to pay for talent, and it just amazed me that more teams did not do that — especially if you’re a team trying to rebuild.”

Along with other aggressive clubs such as Pittsburgh, Boston and Kansas City, the Nationals did, especially from 2009 through ’11 when they stole draft headlines and consistently paid over MLB’s recommended value for the draft slot — even for lower-round picks. They hit their crescendo last year.

“If Purke, Brian Goodwin, Alex Meyer and Rendon were in the 2012 draft, based on what I’ve seen in the country so far, they’re all top-10 picks,” Kline said. “You have to overpay because of their value, but it was the last and final opportunity to do that.”

The penalties for teams spending in future drafts the way the Nationals have in recent years now are more severe. If Washington was to execute its 2011 draft under the new rules, it would lose two future first-round picks and be hit with a hefty tax.

Translating accolades into wins

The Nationals’ goal from the start never was to have the best farm system and be content. The key is to translate that strength into wins and championships.

Tampa Bay, Boston and Texas have used strong systems to reach the playoffs in recent years. The Red Sox, like the Braves when they won 14 straight division titles from 1991 through 2005, have provided the blueprint on how to sustain major league success while maintaining strong minor league operations.

But many teams can’t get over that hump. That, most say, stems from ownership. When the time is right to begin integrating free agents and spending what it takes to keep the pipeline open, it requires commitment from those writing the checks. The Nationals’ owners say they’re on board.

“Let’s put it this way, we’ve never been shy about the money we’ve spent on scouting, on player development, on draft choices and [free agency],” Lerner said. “I don’t think there’s a question people know we’ll spend the money — whatever it takes, within reason — to build it. But we’re businessmen, too. We’re going to be smart about it. We’re taking the advice of our GM, who we consider the best in baseball, and we’re going to try to do things the right way. I can’t explain it any better than that.”

In recent weeks, as spring training nears, fans have approached Lerner on the street to tell him how excited they are for the coming season. The accolade from Baseball America is just another cause for optimism.

“The question is: Are we there yet?” Lerner said. “I think what the fans need to hear is we’re very confident now that we’re going from that development stage … to a stage where we’re going to be winning and hopefully winning regularly.”

• Amanda Comak can be reached at acomak@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.