The Obama administration’s increasing reliance on special operations forces with a stagnant budget has sparked concern among the elite units that they will be asked to do too much with too little.

The forces will be conducting missions in 120 countries by year’s end, up from about 75 currently. This activity is increasing as the U.S. Special Operations Command’s budget is set to remain flat.

The command’s fiscal 2013 budget request is $10.4 billion — essentially the same as its current budget. In 2011, its budget was $12.1 billion.

Defense Secretary Leon E. Panetta said last month that as U.S. troops gradually withdraw from the war in Afghanistan, there will be “more opportunities for special operations forces to assist and advise our partners in other regions.”

“There is some concern that the SOF community is not going to be robust enough to maintain these high-demand operations indefinitely,” said retired Lt. Gen. David Barno, a former Army Ranger and former commander of U.S. and coalition forces in Afghanistan.

In a Feb. 14 Foreign Policy article titled “SOF Power,” Gen. Barno said the Obama administration has not adequately addressed important questions about the impact on the culture of special operations forces.

In a Feb. 14 Foreign Policy article titled “SOF Power,” Gen. Barno said the Obama administration has not adequately addressed important questions about the impact on the culture of special operations forces.

Dedicated support

For instance, high demand for special operations over the past decade has contributed to a shortage of adequate support, such as helicopters dedicated to special operations forces, he said.

In August, 30 troops, including 22 Navy SEALs, were killed in Afghanistan when Taliban fighters shot down their helicopter — a Chinook, which typically is used for heavy transport and flown by a conventional crew.

Although the type of helicopter and crew had nothing to do with the shootdown, Gen. Barno said, it only makes sense that highly trained specialized troops should deploy into combat in an helicopter dedicated for special operations.

“You always want to fight with the same people you train with,” said Gen. Barno, now a senior fellow and adviser at the Center for a New American Security.

According to a recent Congressional Research Service report, the special operations forces may expect even less support.

“In light of anticipated ground-force cuts, the services might be hard-pressed to establish and dedicate enabling units to support [Special Operations Command] while at the same time providing support in-kind to general purpose forces,” the Jan. 11 report stated.

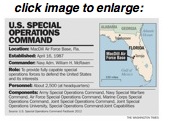

Special Operations Command, based in Tampa, Fla., has about 66,000 military and civilian personnel. At any given time, 54,000 are training or redeploying, and 12,000 are deployed around the world. About 9,000 are in Afghanistan.

The command expects to add about 8,800 troops over the next four years — 2,500 this year, 2,300 in 2013, and 2,000 in 2014 and 2015.

The selection process can take weeks, and training generally takes at least two years, so the new troops will not provide immediate relief for the majority of special operators that are deployed.

’It has taken a toll’

With the forces spread out around the world, the Obama administration also is counting on them to train Afghan national security forces in the war zone.

“As the conventional Army and Marines begin to draw down in Afghanistan, they will get a bit of a breather. But Special Operations Forces won’t. They will continue to carry the fight,” said Gen. Barno.

In the aftermath of the Sept. 11 terror attacks, Special Operations Command has raced to keep pace with soaring demand for its services: Its personnel numbers have nearly doubled, its budget has tripled and the number of its deployments has quadrupled.

After all, the forces perform a wide range of combat and noncombat missions — reconnaissance and surveillance, hostage rescue and recovery, special security, civil affairs, education and training — most often in hostile or sensitive territory.

It is not uncommon for special operations troops to have deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan more than 10 times over the past decade, as well as participating in deployments to other places, such as Colombia or the Philippines.

“The pace of deployments for the past decade has been relentless,” said the wife of a special operations member who asked to remain anonymous so as not to identify her husband. “Our lives have been a nonstop roller coaster of deployments and reintegrations, and it has taken a toll on both of us and certainly on our marriage and on his relationship with our children.”

She said that for most of the past decade, she and her husband have spent less than six months together between deployments, and those months were usually filled with training trips that also took him away from the home.

“Many of our friends in the special operations community have gotten divorced, several of the Special Forces wives I know have attempted suicide, and many of the children in our community have exhibited serious behavioral and emotional problems,” she said.

Gen. Barno said: “Conventional forces can look ahead and see the light at the end of the tunnel, but special operators look ahead and see the continued demand as far as they can see. They can’t see a light at the end of the tunnel.”

Last month, Navy Adm. William McRaven, commander of Special Operations Command, sent an email to special operations members and their families, and later toured several installations to discuss quality-of-life issues.

He has pledged to improve the predictability of deployments for individuals. A task force, created by Navy Adm. Eric Olson, former commander of special operations, is looking into what programs exist to help the special operations community.

“Ensuring the health of U.S. Special Operations Command — that means doing everything possible to take care of its service members and their families — is a top priority,” said Pentagon spokesman James Gregory.

• Kristina Wong can be reached at kwong@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.