When Wal-Mart was looking for property to develop in Ward 6 for one of its four proposed D.C. stores, it didn’t have to go very far.

Politically connected lawyer and lobbyist David W. Wilmot, the company’s man in the District, had a financial interest in city-owned property on New Jersey Avenue in Northwest that he and his business partners had allowed to lay fallow for 21 years — renting it to the federal government as a parking lot for 18 of them.

Not many lobbyists can be players in deals they are lobbying for on behalf of a company like Wal-Mart Stores Inc., much less one involving city land and a long-term tenant who has failed to deliver on promises to a city in need of redevelopment.

But there aren’t many David Wilmots in D.C. business and politics.

D.C. officials privately acknowledge that it takes connections to sit on city property for decades without developing it, saying such “land banking” often depends on faulty land-use policies and the exploitation of a dysfunctional city bureaucracy.

“I can’t speak to why this property was allowed to languish this long,” Jose Sousa, a spokesman for Victor Hoskins, deputy mayor for economic development, said about the 161,000-square-foot parcel currently assessed by the city at $72 million. “It’s not the tact we take with our current project inventory.”

When first contacted months ago about Mr. Wilmot’s financial interest in the New Jersey Avenue property, Wal-Mart spokesman Steven Restivo said he was unaware of such a stake. But as ties between Mr. Wilmot and the tenant of record — the Bennett Group — became harder to ignore, Mr. Restivo confirmed that Mr. Wilmot disclosed his financial interest.

Mr. Restivo deferred further questions to the Bennett Group.

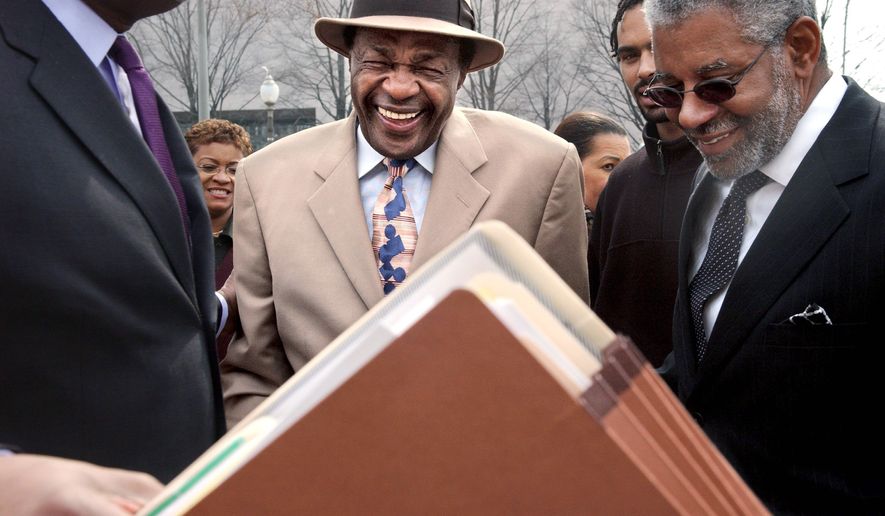

The precise relationship between Mr. Wilmot, a power broker since the first Marion Barry administration with interests in group homes for the developmentally disabled to parking lots, and the Bennett Group, headed by LuAnn Bennett, widow of Richard A. Bennett Jr. — who was a law partner of Mr. Wilmot — is unclear.

Ms. Bennett, now in the process of divorcing Rep. James P. Moran Jr., Virginia Democrat, declined requests for comment. Mr. Wilmot did not return calls or emails.

’Nature of the business’

Charles Maier, a spokesman for the Bennett Group’s financing partner, JBG Cos., said neither the Bennett Group nor JBG has an obligation to disclose private relationships. “It’s just the nature of the business,” he said.

Yet what appears to be previously undisclosed financial interests in land banking arrangements can get messy, and the suddenly attractive piece of dirt between New Jersey Avenue to the west, I Street to the north, H Street to the south and the Gonzaga College High School campus to the east is in the midst of historically blighted neighborhoods near North Capitol Street.

So questions have been raised about how Mr. Wilmot and his partners were able to collect tax-free rent on D.C. land for years.

Now his client is planning a multimillion-dollar project, featuring a Wal-Mart store that sells groceries, 10,000 square feet of first-floor retail set aside for small businesses and several hundred apartments, some of which will be workforce housing.

Mr. Wilmot just happens to be on both sides of the deal.

In 1990, after suing the city for a deal gone bad, Mr. Bennett and former Washington Redskin Brig Owens received a 99-year ground lease on the property as part of a settlement. The lease called for development of a prevocational school, and a zoning application called for construction of three office buildings and a day care center/nursery school/tutoring center.

Zoning records show that a “Minority Educational Foundation” was to be funded with $2 million “not later than two years after the ground lease commencement.” The foundation was to be headed by a board that included Mr. Bennett, Mr. Owens and Mr. Wilmot, the records state.

Under the ground lease, Mr. Bennett and his partners gained exclusive development rights. In return, they would pay the District $250,000 a year for the first two years, $10 million on the second anniversary of the lease date, and $2 million annually from years three through 10.

Annual rent would increase to $2.5 million in years 11 through 20, and to $3.1 million in years 21 through 30, the lease states.

The District would never see buildings go up, nor payments close to what the lease called for. Rather, in 1993, the Bennett Group, with approval of the D.C. government, began subleasing the property to the U.S. Government Printing Office as a parking lot for the GPO’s 475 employees, according to the agency.

Rent reduced

In 1995, in a lease amendment retroactive to 1993, the District reduced rent to $15,000 per month until the Bennett Group began construction of the buildings it had promised. Thereafter, annual rent would increase to $2 million for the next 20 years, the amendment states.

In 1999, a lease memorandum specified that the $10 million lump-sum payment would not be due until 2018.

A second lease amendment in 2007 required the Bennett Group to acquire building permits and break ground on a building by Dec. 31, 2010, or face financial penalties. By then, the Bennett Group had steadily increased the GPO’s monthly rent for years, according to the GPO, which put the current rent at $56,000 a month.

According to the deputy mayor’s office, the District since 1990 has collected about $5.5 million in ground rent and a “possessory interest tax” enacted in 2000 as a means of raising revenue on otherwise tax-exempt commercial property.

But, according to the GPO, the Bennett Group has received more than $5 million in parking lot rent since 2001 — breaking even before factoring in eight years of tax-free rent from the 1990s. Land records also show that the Bennett Group borrowed $1.5 million against the property in 2007 and paid off a promissory note the next year.

In contrast, a review of the ground lease shows that had the Bennett Group performed under its agreement, it would have been required to pay the District more than $41 million by now.

The Bennett Group’s control of the New Jersey Avenue property came as the District was in a state of chaos at the end of the first Barry administration. The Barry era of the 1980s had presaged a re-examination by city officials of District land use.

Soon after Sharon Pratt was elected D.C. mayor on a promise of reform in 1990, she sought to address the glut of city property that had not been taxed while in the hands of private developers for years, said Merrick Malone, Ms. Pratt’s deputy mayor for economic development.

“I forced developers to turn over everything that had been land banked throughout the 1980s,” Mr. Malone recently told The Washington Times. “I told ’em to build, pay or get off. A lot of land came back to us,” he said, pointing to the later redeveloped Gallery Place and Columbia Heights sections of town.

But when asked about the ground lease at the Bennett Group’s New Jersey Avenue site, Mr. Malone said he could not recall.

“I don’t know how I missed that one,” he said.

Former mentor

Pressed for details, Mr. Malone does recall, however, that Mr. Wilmot, his former mentor at Georgetown Law School who served on the transition committee that recommended him for his Cabinet-level post, had been law partners with Mr. Bennett.

“I tried to break some of those agreements and take back the land, but some of them were ironclad,” he said. Asked to defend either the deal with the Bennett Group or the principle of land-use reform, Mr. Malone did both: “It doesn’t appear they did anything wrong except outsmart the District. I’m pro-development, but it sounds like a brilliant business move.

“But it’s unbelievable that the District could have so much land off the tax rolls, then to let people land bank on top of it,” he said.

Asked about Mr. Wilmot’s dual role as land banker and Wal-Mart lobbyist, now that two decades later his client and his partners in the Bennett Group are developing the property, Mr. Malone said, “I don’t know what the hell that is. That’s interesting.”

Ms. Pratt, a one-term mayor, seemed similarly perplexed.

“It’s not in the city’s interest to tolerate land banking if it’s not centered around a clear set of objectives,” she told The Times. “To just allow such arrangements to continue ad infinitum without strategic goals? I don’t understand it.”

Successors to the Pratt administration continued to wrestle with the District’s untaxed and underdeveloped land problem, while Mr. Wilmot and the Bennett Group continued to collect tax-free rent from the GPO throughout much of the 1990s.

Kenneth R. Kimbrough was the District’s chief property manager from 1998 to 2000 under Mayor Anthony A. Williams. By then, the city’s finances were in shambles after the last of Mr. Barry’s terms as mayor and a congressional control board was overseeing city finances.

Mr. Kimbrough said a mandate of the era was to establish a central agency and database to oversee land dispositions. Reviewing deals that were cut during the Barry administration, he said, “We found a lot of goofy transactions, to be kind. Like, why’d he do that?

“Our marching orders were: Clean this mess up,” he said.

Payment postponed

Yet the 1999 lease memorandum signed by Mr. Kimbrough simply summarized the ground lease between the District and the Bennett Group and allowed the $10 million lump-sum payment that had been due in the second year of the lease to be postponed until 2018.

“I have a vague recollection,” he said, unable to offer details of why the decision was made.

Meantime, the Bennett Group sharply increased the parking lot rent from roughly $400,000 per year in 2001 to more than $675,000 in 2010.

In 2007, under Mayor Adrian M. Fenty, the District imposed a $750-per-day penalty as of Jan. 1 of this year for each day the Bennett Group allowed the property to languish. After Jan. 1, 2013, the penalty increases to $1,500 per day.

“You can argue correctly that 20 years is an incredibly long time for that property to lay fallow,” said Lars Etzkorn, the District’s chief property manager at the time.

Though he noted that market conditions can be a determining factor in urban redevelopment, Mr. Etzkorn, now a director of finance and economic development for the National League of Cities, concluded that the Bennett Group was able to take advantage of the District’s less-than-optimum land-use practices.

“That’s kind of crazy,” he said. “Why wasn’t the city allowed to share in some of the revenue until development occurred?”

Mr. Restivo, Wal-Mart’s spokesman, declined to say how the company identified the New Jersey Avenue property as a development site. He provided an article from The Washington Post that profiled the company’s real estate broker, John Meyer, and insisted it was self-explanatory.

But the article does not address Wal-Mart’s interest in the Ward 6 parcel it intends to develop as part of a multiuse complex. It does identify, however, the official responsible for marketing available property to retailers seeking to develop stores in the District.

Keith Sellars, senior vice president for the Washington, D.C. Economic Partnership, which works with the deputy mayor’s office, said he recalls discussing with Wal-Mart three of the four parcels slated for development - but not the property at New Jersey Avenue.

Mr. Meyer told The Times that a developer told him of the property some time ago, but he could not recall when and declined to identify the developer. He said he learned of the property before he met Mr. Wilmot and that he could not recall being informed of the lobbyist’s financial interest in the property.

“Mr. Wilmot had nothing to do with this,” he said.

Yet in discussing the history of the property, Mr. Meyer acknowledged what D.C. officials have learned the hard way: that Mr. Wilmot is perhaps the foremost expert on the property at New Jersey Avenue and H Street Northwest.

“That’s who you need to talk to,” he said.

• Jeffrey Anderson can be reached at jmanderson@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.