Trying to balance the need to rein in deficits with his belief that spending now on education and other priorities will pay off in the long term, President Obama on Monday sent Congress a $3.7 trillion budget blueprint for 2012 that makes some short-term fixes but puts off heavy lifting on Social Security and Medicare.

The budget acts as an update on the current fiscal year, as well as a plan for the future, and it shows the federal government will run a record $1.645 trillion deficit in 2011, slimming down to $1.101 trillion in 2012 and continuing the red ink for the foreseeable future, though at lower levels.

After massive spending during his first two years in office, Mr. Obama proposed some tax increases and strategic spending cuts for 2012, such as in low-income energy assistance and student aid. But he also called for boosting spending on transportation and education - needs the president said cannot be sacrificed even in the face of the deficit.

“As we move to rein in our deficits, we must do so in a way that does not cut back on those investments that have the biggest impact on our economic growth, because the best antidote to a growing deficit is a growing economy,” Mr. Obama wrote in the budget he submitted. “So even as we pursue cuts and savings in the months ahead, we must fund those investments that will help America win the race for the jobs and industries of the future - investments in education, innovation, and infrastructure.”

That approach, though, puts him on a collision course with congressional Republicans, who are still working on the overdue 2011 spending bill. The House GOP has called for about $60 billion in cuts in 2011 alone, including energy assistance, student loans and offices across the government.

Republicans called Mr. Obama’s budget a “missed opportunity” to cut.

“This budget ignores the problems,” said House Budget Committee Chairman Paul D. Ryan, Wisconsin Republican. “This budget does more spending, more taxing, more borrowing, and at the end of the day, if we don’t turn this around, that’s going to cost us jobs. It’s going to cost us prosperity, and it’s going to cost our country its credibility.”

Even key Democrats questioned the president’s failure to tackle the major causes of ballooning spending.

Senate Budget Committee Chairman Kent Conrad, North Dakota Democrat, said the president’s budget “gets it about right in the first year,” but doesn’t cut it for the future.

“We need a much more robust package of deficit and debt reduction over the medium and long term,” he said. “We need a comprehensive long-term debt-reduction plan, in the size and scope of what was proposed by the president’s fiscal commission. It must include spending cuts, entitlement changes, and tax reform that simplifies the tax code, lowers rates and raises more revenue.”

Mr. Obama’s 2012 budget comes as spending and deficits have become the dominant issue in Washington, and as Congress rushes to complete the 2011 spending bills that are already more than four months overdue.

The administration acknowledges its proposal still includes hefty deficits, though it said those deficits will be $1.1 trillion less, thanks to the cuts and tax increases Mr. Obama is proposing.

White House officials said two-thirds of that $1.1 trillion comes from spending cuts and one-third from tax increases, though outside analysts were having difficulty verifying those numbers Monday because of the complexity of the budget.

Overall, the debt would grow under his plan from just over $14 trillion now to nearly $21 trillion in five years.

Mr. Obama did call for letting the Bush-era tax cuts for the wealthiest expire, and for the estate tax to rise to 2009 levels.

The White House said Mr. Obama is willing to take on big-ticket items like Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid, but won’t do it alone. Officials said they are looking for a bipartisan process to move those issues forward.

But the White House did not include most of the recommendations of the fiscal commission Mr. Obama himself formed last year and charged with making recommendations for closing the deficit.

Even as Republicans and some Democratic budget hawks say he’s missed a chance to fix the country’s finances, Mr. Obama is taking heat from the political left for cutting too quickly in the midst of a still-sluggish economy.

“The proposed budget does too little and turns too quickly toward deficit reduction,” said John Irons, research and policy director at the Economic Policy Institute.

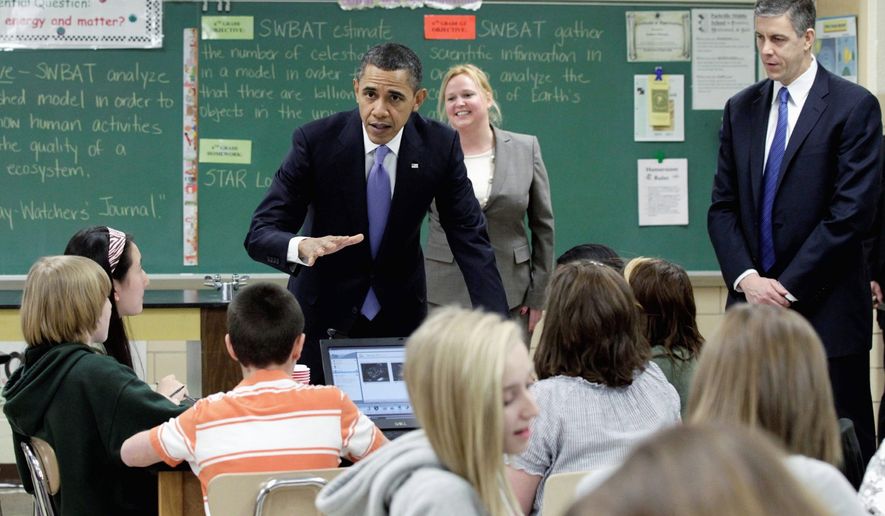

Education is a cornerstone of Mr. Obama’s new “win the future” message, and it’s one of the clearest winners in his budget, which boosts overall education spending by 11 percent and keeps the maximum Pell Grant at $5,550 per participating student.

That almost surely puts Democrats on a collision path with Republicans, who want to cut the Pell Grant program by $845 million this budget year. In a preview of that clash, education groups seemed to side with Mr. Obama on Monday, with the Project on Student Debt urging Congress “in the strongest possible terms not to cut the maximum Pell Grant and to preserve this lifeline to opportunity and prosperity.”

The administration’s education budget also includes $900 million for Race to the Top, Mr. Obama’s marquee education initiative, and $600 million in school-turnaround grants. At the same time, the proposal would increase the tab for graduate students who rely on government-subsidized loans by eliminating federal subsidies so that interest would start accruing immediately, as opposed to after graduation.

Other brewing fights include a separate production line for an alternate engine for the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, which the Pentagon says isn’t needed but which Congress has funded over Mr. Obama’s objections, and over high-speed rail. The president is seeking to pump tens of billions of dollars into rail projects, but House Republicans have called for going in the other direction and cutting existing funding.

One of the more controversial moves contained in Mr. Obama’s budget is a $2.5 billion reduction in low-income energy assistance. Office of Management and Budget Director Jacob “Jack” Lew defended the cut Monday by pointing out that energy prices were higher when lawmakers decided to increase the program by $2.5 billion a few years ago.

“This is a very hard cut,” he told reporters. “But we can’t just kind of cruise at a historic high spending level when we’re trying to make these very difficult savings.”

But Robert Greenstein, executive director of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, said the government’s own estimates predict energy prices will return to 2008 levels, meaning the higher payments would still be justified.

Still, Mr. Greenstein gave the administration credit for signaling that long-term budget challenges, such as lowering the alternative minimum tax and making payments to doctors who treat Medicare patients, must be solved for the long term.

In both those cases, the president used long-term budget savings to pay for short-term fixes.

Obama budget: $3.7 trillion

FY '12 blueprint calls for key 'investments'; red ink surges

Please read our comment policy before commenting.