Tom Coburn’s reputation preceded him throughout the Capitol. He was a cantankerous troublemaker who was tough to work with and more interested in blowing things up than getting things done — and that reputation was completely wrong, just about everyone who worked with him quickly came to realize.

While he was willing to stand in the way of spending that he thought unnecessary, he was also a master legislator.

With a single amendment to a bill in 2010, he saved the government $262 billion and counting. He made a cottage industry out of spotting ridiculous-sounding spending items, such as the “Bridge to Nowhere” project in Alaska. His work on the Senate’s oversight committee brought down the largest Social Security disability fraud ring in history.

Mr. Coburn, a medical doctor turned politician who served six years in the House and a decade in the Senate, died Saturday at age 72 after a lengthy battle with cancer, leaving one of the most substantial legacies in recent congressional history.

To those who knew him best, Mr. Coburn’s virtuoso legislative abilities were exceeded by his decency.

“I’ve never met another politician like him. His honesty, devotion to facts and reason, his strength, his intellect and his genuine warmth will always be with me. His true friendship will be a gift I will treasure forever,” said Erskine Bowles, who was chief of staff to President Clinton and got to know Mr. Coburn while working on a commission to cut the deficit.

Mr. Coburn won election to the U.S. House as part of the Republican sweep in 1994, when he captured a Democrat-held seat. He served three terms and then left to keep his term limit pledge. The seat was promptly won by a Democrat.

Four years later, he sought Oklahoma’s open Senate seat. Republican leaders worked against him in the primary, but he won. In the general election, he beat Rep. Brad Carson, the Democrat who had taken over his House seat.

Alan Frumin, who was parliamentarian in the Senate during most of Mr. Coburn’s tenure, said people warned him of the impending storm after Mr. Coburn’s election in 2004. He was prickly and tough to work with, the story went.

“Suffice to say it, they were wrong,” Mr. Frumin said.

“We developed such respect for his way of doing business, and respect morphed into affection, and I say that as somebody who, he certainly put us through our paces,” Mr. Frumin said. “He was dogged, he was thorough and he was good to his word on everything. He was a force to be reckoned with.”

Setting aside the late Sen. Robert C. Byrd, the West Virginia Democrat who literally wrote the book on the history of the Senate, Mr. Coburn was in a class of his own when it came to learning and deploying the chamber’s rules.

Few senators bother to pay attention to the rules. Of those who do, some delegate to their staff while others learn it all themselves. Mr. Coburn did both.

’I’m not coming to Washington to make friends’

By his own measure, Mr. Coburn failed in 2010 when the Senate was debating yet another debt limit increase and he came to the floor with an amendment demanding $120 billion in spending cuts. He figured government had at least enough duplication that agencies should be able to sweat out that much.

Democrats who controlled the chamber resisted, and so did some Republicans.

Mr. Coburn settled for a study, and Congress ordered the Government Accountability Office to produce a report on redundancies.

Yet that failure may be the single most successful act of budget-cutting in decades. That Republican study became known as the duplication report, a yearly page-turner of government redundancies that as of last year saved $262 billion — “and counting,” said Gene Dodaro, who, as comptroller general, is head of the GAO.

The GAO’s duplication webpage has been viewed more than 280,000 times. The reports have more than 165,000 views on PDF and have been downloaded nearly 45,000 times.

When the next report is released this spring, the $262 billion figure will be even higher.

“The gift that keeps on giving, and it will for a long time,” Mr. Dodaro said.

One of Mr. Coburn’s principles drilled into staff was that they shouldn’t be afraid to fight and lose. Sometimes you won the war by losing a few choice battles.

But they were also drilled to always treat legislative opponents with respect, to try to find common ground and to outwork everyone else.

“When I met Dr. Coburn in November 1994, he got right up in my face and said, ’Are you sure you want to work for me? I’m not coming to Washington to make friends,’” recalled Roland Foster, Mr. Coburn’s legislative director. “After being elected to the Senate, a Senate staffer advised me not to work for him because no one was going to work with him. After irritating nearly everyone in Washington for 20 years, he left the Senate at a time of extreme partisanship but with more friends on both sides of the aisle than nearly anyone else left in politics.”

Coburn staffers figure they wrote more than 1,000 amendments to cut spending during his 10 years in the Senate.

Most of the amendments were easily defeated or, more often, never even got a vote.

One of those failures was the Bridge to Nowhere, a span in Alaska that was to be built to reach Gravina Island, with a permanent population of perhaps 50. Alaska’s congressional delegation inserted an “earmark” into a bill directing $223 million to the project. The Alaskans said the bridge was needed to replace a less reliable ferry service.

After Hurricane Katrina slammed the Gulf Coast, Mr. Coburn called on Congress to cut the bridge money and use it to rebuild a bridge in Louisiana. His amendment was crushed by a 82-15 vote.

But the bridge was never built. Mr. Coburn had made the project too toxic.

Several years later, Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin canceled the project and said the money would be used elsewhere.

Earmarks never recovered from the bad press and were eliminated by 2011.

Silly science and other crusades

Mr. Coburn made “shrimp on a treadmill” famous when he highlighted a federally funded science research project that involved running shrimp on a specially built treadmill designed to test how shrimp absorbed oxygen under stress.

When a video of the shrimp surfaced, Mr. Coburn pounced and dubbed it a waste of taxpayer money.

The Washington Times reached out to the study’s author but got no response.

Mr. Coburn also challenged the Social Security disability of a man who lived as an “adult baby” who slept in diapers in an adult-size crib and collected government benefits, even though he acknowledged he had some computer and woodworking skills.

When Democrats called a press conference to complain that Mr. Coburn was blocking a bill that they wanted Congress to pass, he showed up and sat in the front row alongside the press.”I’m going to enjoy the festivities,” he told reporters.

Mr. Coburn was the chief sponsor of Sen. Barack Obama’s biggest legislative accomplishment: the Federal Funding Accountability and Transparency Act of 2006. Mr. Obama attended the ceremony at the White House where President George W. Bush signed it into law. The measure created USASpending.gov, which is still the best way to track government contracts and disbursements.

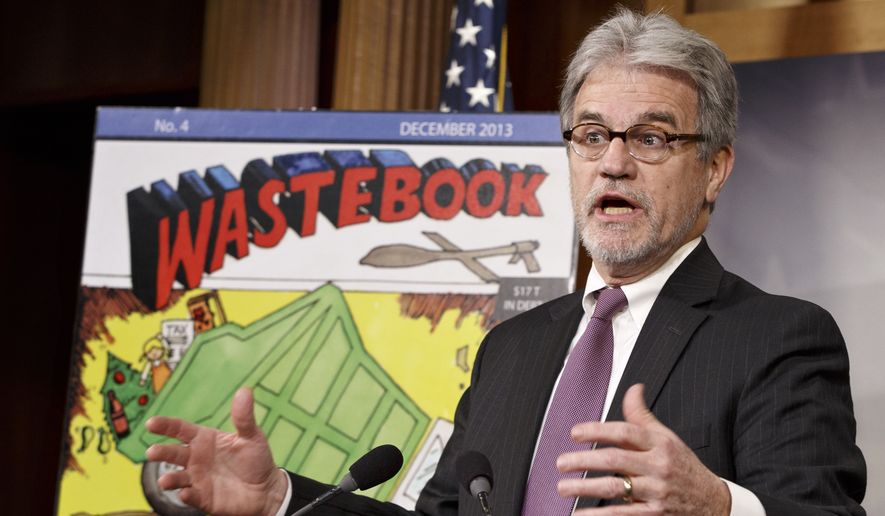

Already famous in Washington, Mr. Coburn gained national attention with his annual “Wastebook,” which highlighted silly spending. Late-night comedians ate it up.

Those who worked with Mr. Coburn said he was never cheap. He gave his best and expected that of those around him.

“I loved working with him. He actually made it easy to do so,” said Mr. Bowles, who worked with Mr. Coburn on a committee to make suggestions for cutting the deficit.

“From Day One, he was completely transparent, honest and straightforward with me. But he didn’t just give me his trust; it was something I had to earn over time,” Mr. Bowles said. “But once he did feel confident that Al and I were as committed to real fiscal responsibility and reform as he was, he educated us, directed us and led us to ideas and solutions we would never have found without his direction, guidance and expertise.”

The outsider

That’s not to say Mr. Coburn wasn’t willing to mix it up.

Most freshman senators are content to lie low and get a feel for how the Senate operates. Some wait months before delivering their maiden speeches on the floor.

Mr. Coburn didn’t bother with a maiden speech. He just began blocking other senators’ bills. Within a few months of taking office, Roll Call, a Capitol Hill newspaper, said Mr. Coburn had put a “hold” on hundreds of pieces of legislation.

Don Ritchie, historian emeritus for the Senate, said Mr. Coburn probably holds the all-time record for holds.

Some of Mr. Coburn’s friends on Capitol Hill seemed to misunderstand him and labeled him a hard-liner. The reality was far more complex.

He was a champion for HIV/AIDS patients, though in his own way, said Scott Evertz, who was Mr. Bush’s director of AIDS policy.

“Being concerned about an epidemic or a pandemic, and being fiscally conservative, are not mutually exclusive,” Mr. Evertz said. “I don’t think there was anyone that could quarrel with the fact that he cared about people living with HIV.”

Mr. Evertz recalled a meeting of the president’s advisory AIDS council where Mr. Coburn passed out a book, “Sexual Ecology,” written by a gay rights activist. The book was rather graphic and stunned liberal and conservative members. Mr. Evertz said Mr. Coburn found the book scientifically sound and therefore deemed it worthwhile.

In 1996, when Republican presidential nominee Bob Dole was refusing a campaign donation from the Log Cabin Republicans, whose members advocate for gay rights, Mr. Coburn spoke at the group’s event, Mr. Foster said.

Mr. Foster said Mr. Coburn had skepticism of big business as well as big government. Among the measures he sponsored were bills to prohibit insurance companies from canceling policies for those who sought HIV tests. He also teamed up with Sen. Bernard Sanders, Vermont independent, on legislation to allow Americans to access prescription drugs sold at lower prices in other countries.

“The real reason he was so dangerous is because he was so independent and had his own opinions and solutions on everything,” Mr. Foster said.

Those solutions showed up in Mr. Coburn’s oversight reports. One report exposed the massive Social Security scam run by Eric C. Conn, a lawyer in Kentucky who filed thousands of bogus disability applications. Had the fraud not been stopped, it could have accounted for $1 billion in lifetime benefits that shouldn’t have been paid.

Conn is now in prison serving a 12-year sentence for the fraud and a 15-year sentence for escaping home confinement.

’A special, special man’

Many members of Congress, when they come to Washington, go through a transformation. For the first few years, when they talk about “we,” they usually mean their constituents back home. Eventually, when they say “we,” they mean themselves and other members of Congress.

Mr. Coburn didn’t succumb to that.

He made a three-term pledge when he first ran for the House in 1994 and stuck to it. He left the chamber after the 2000 election.

When he ran for the Senate, he imposed a two-term pledge on himself. He ended up staying just 10 years and left early because of poor health.

“Tom Coburn was a special, special man,” said Sen. Ben Sasse, Nebraska Republican. “He was a Christian and a father and a husband, and all of those identities were much more important to him than where he got his paycheck.”

Mr. Coburn took pains to keep his ties to his Oklahoma life while in Washington — including delivering babies as part of his doctor’s practice.

That sparked another of his fights against the Washington establishment. The Senate ethics committee ruled that Mr. Coburn was violating conflict of interest rules by holding an outside job.

Mr. Coburn then stopped taking payment and said he would work pro bono. The committee rejected that plan, saying he was working at a for-profit hospital so it presented a conflict of interest.

He ignored the committee and continued his practice.

A little-known fact, according to a longtime aide, is that one of the babies Mr. Coburn delivered was future “American Idol” winner Carrie Underwood.

• Stephen Dinan can be reached at sdinan@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.