OPINION:

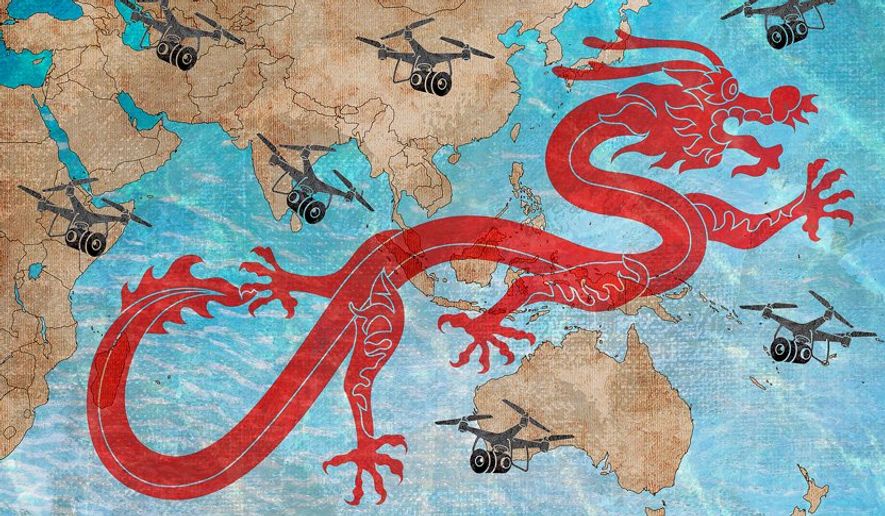

As the rules of the sovereignty endgame are revved up for reconnaissance and surveillance of the environment and Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs), the increased use of unmanned aerial vehicles or non-lethal drones emits more than a steady buzz in the latest foreign policy salvos among claimant nations against Beijing’s control of the South China Sea.

A few months ago, the Pentagon announced the $47 million sale of 34 ScanEagle drones, made by Boeing, to the governments of Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam. As many as 12 unarmed drones and equipment are on the way to Malaysia, followed by Indonesia and the Philippines with eight each and Vietnam six, for maritime surveillance and intelligence gathering.

Drone technology is on the rise. The Business Research Company (TBRC), places the global commercial drone market at $3.45 billion in 2018 and at $7.13 billion in 2022. Asia Pacific’s anticipated leap forward as a growth market is because of the rapid increase in awareness for civilian drone applications and relaxation by governments for the use of UAVs for commercial purposes and military applications related to border security.

This rally around drones is against the specter of China fielding a new, far-reaching drone surveillance network in the South China Sea. Their light maneuverable drones are capable of relaying real-time images and video from inaccessible areas to mobile and fixed command-and-control centers, thus reinforcing China’s dominant survey of the contested sea.

At the moment, policy makers and defense analysts seem to agree that non-military threats associated with the lack of access to resources or future environmental disasters are proving to be far more devastating than military threats, since environmental issues cannot be faced by military alliances. As a result, environmental degradation, fishing exploitation, widespread destruction of vulnerable coastal habitats from land reclamation, agricultural and coastal development are considered the real threat to national interests.

“The trend of using UAVs in maritime activities will surely increase given the complexity of issues surrounding the South China Sea,” claims Tran Viet Thai, deputy director-general of the Institute for Foreign Strategic Studies in Hanoi.

As part of an emerging cooperation climate to assess and monitor illegal, unreported, and undocumented (IUU) fishing, search and rescue at sea and scientific surveys, the unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) are well placed to meet those objectives.

And yet, a legal conundrum exists that poses a challenge to the deployment of drones for marine scientific research in another country’s EEZ. Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), coastal nations have sovereignty over marine natural resources within their Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), the area of the ocean extending 200 nautical miles from their coastline. UNCLOS does not permit one nation from performing marine scientific research in another country’s EEZ, but military surveys are allowed with or without the country’s consent. So, no oceanographic surveys, even those conducted by drones, are allowed.

What’s clear is that “the proliferation of drones will reset the rules and norms governing surveillance and reconnaissance and invite new counter-measures that may paradoxically increase uncertainty between rivals over the long run,” notes Michael J. Boyle, associate professor of Political Science at La Salle University.

There are more gains from drones since oceanographers examine and monitor marine life and conservation and the technology provides on-demand remote sensing capabilities at low cost and with reduced human risk from naval patrols and aggressive para-military vessels.

ASEAN member states are among the world’s biggest sources of plastic pollutions. More than half of the plastic waste in the ocean comes from only five Asian countries: China, Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam and Thailand. That’s why Plastic Tide’s director, Peter Kohler, is committed to engaging an army of drones and an algorithm to remotely detect hotspots in the oceans, including the South China Sea.

With an estimated 4.8 to 12.7 million metric tons of plastic dumped into the sea annually, there’s a demand for the adoption of drones and remote sensing technology for the detection of floating marine plastics.

With an increase in the available drones operating, the harnessing of Mr. Kohler’s technology can propel the initiative to document marine plastics pollution in real time; thereby supporting regional environmental policies aimed at monitoring marine conservation areas.

Since 2013, China has dredged-up more than 3,000 acres across seven features that reveal a larger footprint of disputed claims in the Spratly and Paracel Islands. These include long-range sensor arrays, port facilities, runways, drones, and the latest in technology capable of gathering big data on the environment for monitoring of industrial pollution, marine plastics, marine scientific research and humanitarian assistance and disaster relief.

Programs like Duke University’s Marine Conservation Ecology Unmanned Systems Facility helps researchers and scientists navigate the complicated technology and regulations associated with drone-based ocean research projects and resource collaboration.

The geopolitical lens in the South China Sea remains fuzzy at best, because some defense analysts encourage weapons development, while a growing science-led chorus thinks it’s a better security bet to monitor the environment.

• James Borton is an independent writer and a non-resident fellow at Tufts University Science Diplomacy Center.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.