OPINION:

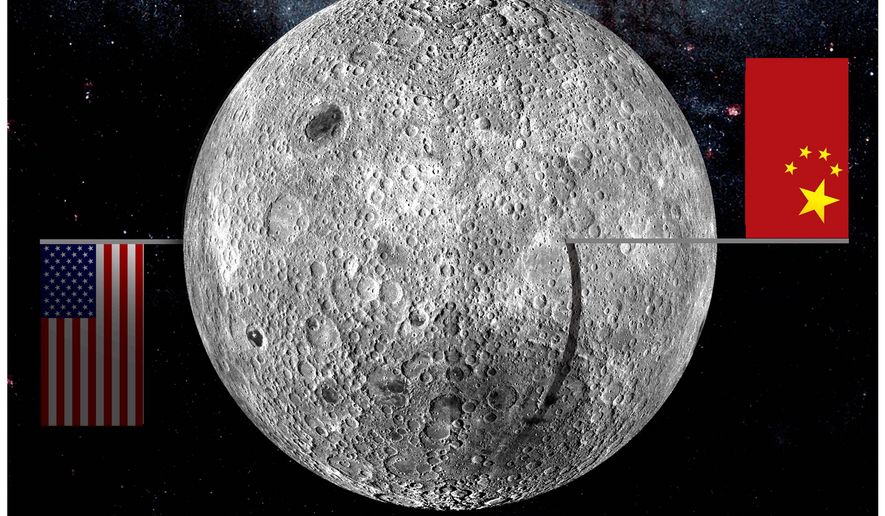

China’s successful landing of its “Chang’e-4” probe on the far side of the moon on Jan. 3 was a first in space exploration. The landing is much more than that. In the context of other Chinese actions, it represents a significant shift in Chinese thinking, which means we need to rethink our approach to space.

It has been nearly 50 years since America’s first manned moon landing and 47 years since the last. Since then, America has limited our ambitions in space to launching satellites, conducting experiments in orbit with the now-defunct space shuttle program, and manning and supplying the International Space Station, an enormously expensive boondoggle.

In those five decades, our strategic thinking has shifted away from space. Presidents don’t speak about a “space race,” as they did in the 1960s and 1970s when space exploration was a defense priority. Our focus has been on the technological advantage satellites have given our military and intelligence communities, but the threats to our national security and strategic interests that arise in Earth orbit and beyond have been afterthoughts.

In that same period Chinese thinking — especially in choosing how to present itself as a belligerent or peaceful nation — has changed greatly. That is not to say that China has changed its underlying expansionist strategy, just the way it presents itself to the world.

China’s leader in the early 1990s, Deng Xiaoping, authored the “24-Character” strategy to guide China’s foreign and security policy. As it is usually translated the “24-Character” strategy said, “observe calmly; preserve our position; cope with affairs calmly; hide our capacities and bide our time; be good at maintaining a low profile; and never claim leadership.”

Under Hu Jintao and Xi Jinping, China has gradually slid away from that strategy. Now, under Mr. Xi, China’s foreign and security policies have become more openly and obviously aggressive on earth and in space.

Most importantly, we have to realize that unlike our domestic and international policies, China’s are carefully interwoven. From building and fortifying islands in the South China Sea to threatening Taiwan’s independence and the Chang’e-4 landing on the moon, China’s actions are linked together logically to achieve expansionist military objectives.

Perhaps the best example is China’s “debt trap” diplomacy by which its lending practice is, in nations such as Pakistan, contingent on the Chinese military institutionalizing its presence in the debtor nation.

China’s race to the moon in the new space race has to be seen in that context. As a peer competitor, it chooses in which to compete with us in those fields we choose — not by strategic choice but by lethargy and skewed spending priorities — to neglect.

America’s military is highly dependent on satellites for everything from secure communication to navigation and detection of missile launches by adversaries. China’s technologically-advanced cyberwar capabilities can probably interfere with satellite operations now and China is pushing its technological advantage as fast and far as it can. Our classified cyberwar capabilities haven’t sufficed to deter China and other nations from attempting to breach our satellite systems’ security.

China and Russia have been testing anti-satellite kinetic weapons since at least 2007, when China destroyed an old weather satellite with such a weapon. According to a report released by the director of National Intelligence last year, both Russia and China will have such weapons deployed in the next few years. Our anti-satellite programs lag far behind.

From the first moon missions until the last manned mission to the moon’s surface, we relied on the Saturn V booster rockets, which had about seven million pounds of thrust. We’ve long since lost the knowledge of how to build so large a booster and nothing has replaced it. NASA is developing a new heavy booster rocket comparable to the Saturn V in lift capacity.

The new booster system, called the “Space Launch System,” won’t be ready until the mid-2020s.

China is choosing to continue its military strategy in space. It developed — and is continuing development — of its “Long March” family of boosters, named for Mao Zedong’s year-long retreat in 1934-35 from which he emerged as the leader of Communist China.

The Cheng’e-4 was launched by a Long March 3B rocket. China is developing other, more capable, rockets including the Long March 9, which will have a greater lift capacity than the Saturn V and is planned to fly in the 2030s. It may prove big enough to launch payloads to Mars.

Last year, President Trump ordered the Pentagon to form a sixth military branch, the U.S. Space Force. That order ran aground in Congress because it would take a decade and cost billions of dollars to accomplish. It would have turned into another military bureaucracy vying for defense dollars. The logical substitute, U.S. Space Command, has been formed within the Air Force.

The president shouldn’t let the failed space force initiative divert his attention from the need to create and push through congress a set of national security priorities for our goals in space.

Those priorities should establish specific defense missions, including acceleration of the development of our own anti-satellite weapons, our return to the moon by 2025 and a mission to Mars by 2035, and creation of missile defense systems in earth orbit. There’s a 21st century space race that we haven’t been running. Let’s get out of the starting blocks.

• Jed Babbin, a deputy undersecretary of Defense in the George H.W. Bush administration, is the author of “In the Words of Our Enemies.”

Please read our comment policy before commenting.