Scientists and ethicists on Monday debated the brave, new world of designer babies and gene pool manipulation, heralded by the announcement that a Chinese researcher had delivered the first gene-edited human babies.

“It’s a somber moment because gene editing is a technology of tremendous promise and potential,” Fyodor Urnov, associate adjunct professor of genetics at the University of California, Berkeley, told The Washington Times.

The Rev. Ronald Cole-Turner, a professor of theology and ethics at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary, acknowledged concerns that the Chinese researcher’s work lacked oversight and input from the scientific community, threatening the safety of the patients and alienating the community from the decision-making process.

“Somebody jumps out ahead, it scares everybody who advocates for the science,” Mr. Cole-Turner told The Times.

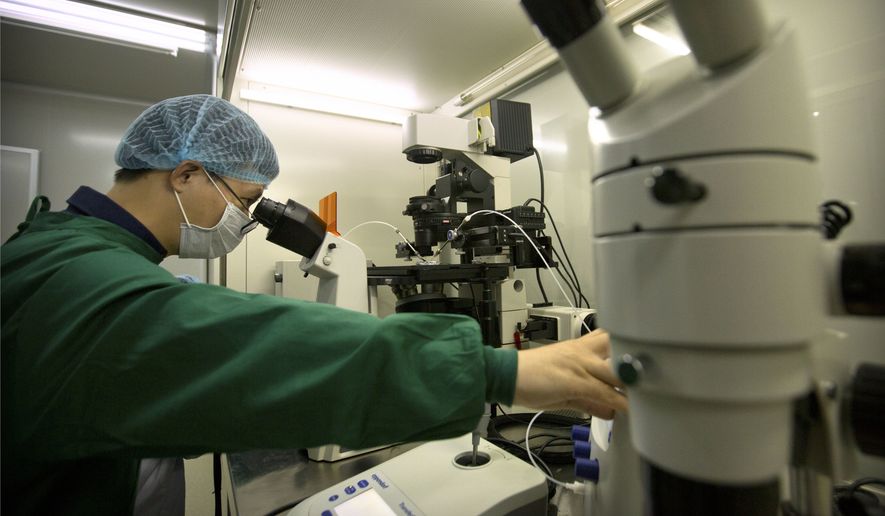

He Jiankui, a researcher at the Southern University of Science and Technology in Shenzhen, China, has claimed to have produced the first genetically modified human babies, twin girls. Their DNA was altered with CRISPR-Cas9 to resist the transmission of HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, he said.

“I feel a strong responsibility that it’s not just to make a first, but also make it an example,” Mr. He told The Associated Press, adding that “society will decide what to do next.”

His claims have not been independently verified, and his findings have not been peer-reviewed. Such experimentation is illegal in the U.S. and some other nations.

Mr. He made the announcement on the eve of a huge conference of leading geneticists and bioethicists in Hong Kong. The three-day conference is meant to further consensus on how to approach genetic modification for traits that can be passed down through generations.

Leading researchers called Mr. He’s presumed work risky, premature and dangerous to the future of scientific discovery.

Mr. Urnov noted that global scientific consensus on genetic editing of embryos has stopped short of implantation and that scientific discovery should be pursued for the most devastating and fatal diseases for which there is an unmet medical need and no viable alternatives.

“The application of editing here was not for that purpose,” he told The Times. “It was essentially to make, for lack of scientific term, a designer baby.”

Mr. He made his announcement Sunday in a YouTube video. He explained how his team used CRISPR to edit out a gene, CCR5, to remove the receptors that bind with HIV, effectively preventing the disease from being transmitted. The editing process took place in a single-cell embryo, fertilized by sperm from an HIV-positive father.

The identities of the twin girls born in China and their parents were kept secret for their privacy, Mr. He said in the video.

Researchers were quick to point out that preventing HIV transmission in offspring is not an “unmet medical need” because countless alternative treatments are available.

“Although I appreciate the global threat posed by HIV, at this stage, the risks of editing embryos to knock out CCR5 seem to outweigh the potential benefits,” said a statement by Feng Zhang, a core member of the Broad Institute of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard and one of the first to harness the power of CRISPR-Cas9.

Knocking out CCR5 will likely render a person more susceptible to West Nile Virus, he said.

“Not only do I see this as risky, but I am also deeply concerned about the lack of transparency surrounding this trial,” said Mr. Zhang, reiterating his support of a moratorium on implantation of edited embryos.

’Test tube’ babies

Jennifer Doudna, a biochemist at the University of California-Berkeley, is — with Mr. Zhang — one of the earlier discoverers of CRISPR. She said Mr. He’s work represents insubordination of the guidelines put forth by the scientific community working in genetics.

“If verified, this work is a break from the cautious and transparent approach of the global scientific community’s application of CRISPR-Cas9 for human germline editing,” Ms. Doudna said in a statement from Hong Kong.

“It is essential that this report not cast an untoward shadow on the many important ongoing and planned clinical efforts to use CRISPR technology to treat and cure existing genetic, infectious and common disease in adults and in children,” she said.

R. Alta Charo, a professor of law and bioethics at the University of Wisconsin, told The Times in an email that human trials first must meet a laundry list of criteria to ensure that test subjects are safe and that results can be used to predict outcomes and generalize to the population.

“This, coupled with the multigenerational effects made possible by germline editing, makes it ever more important to meet key conditions before commencing,” Ms. Charo said.

Organizers of the second annual International Summit on Human Genome Editing also responded to Mr. He’s claims by saying it is unclear whether the Chinese researcher followed global consensus on procedure and ethics in his human experiment, specifically a 2017 report that laid out oversight and transparency in conducting such trials.

“Whether the clinical protocols that resulted in the births in China conformed with the guidance in these studies remains to be determined,” the organizers said in a statement.

“I don’t understand what the rush was,” Mr. Urnov told The Times. He said adults with informed consent easily could have undergone testing that could assure safety and efficacy and could be reviewed by the medical community. “I think they’re thinking about enhancement … about sort of bespoke babies that I don’t think we, as a species, are quite ready for that ethically or safely.”

Mr. He received strong support from one of the leading figures in genetic sequencing.

George Church, a foremost researcher on genetics at Harvard University and the first to outline genome sequencing, likened the importance of the medical breakthrough to the first “test tube” baby born from in vitro fertilization.

“This event might be analogous to Louise Brown in 1978,” Mr. Church said in an email to NPR.

He called the scientific breakthrough “justifiable” and told The Associated Press that HIV presents “a major and growing public health threat.”

Mr. He is expected to present his findings and the outline of his research trial Wednesday at the conference.

“Anyone reading about the birth of twins in China whose embryonic genomes were edited should evaluate the experiment with these criteria in mind,” Ms. Charo told The Times.

Meanwhile, Pittsburgh Theological Seminary’s Mr. Cole-Turner, who is also a United Church of Christ minister, said religious belief is generally in favor of medical technologies that heal and that if genetic editing is used to prevent disease, then the majority of religions would support it.

“Why not view God working through CRISPR if we view God working through chemotherapy?” he said.

• Laura Kelly can be reached at lkelly@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.