It’s been six months since I’ve appeared in these pages. That gap hasn’t been about a boycott or a contract dispute. Actually, The Washington Times has been rather generous, giving me that time to finish a book, get it cleared through the intelligence community review process and then endure an aggressive countrywide book tour organized by my publisher, Penguin.

For a career government guy, that was literally quite a trip. And I’d like to share a few thoughts about it before launching in later follow-on columns into the host of intelligence issues still out there.

The book was called “Playing to the Edge: American Intelligence in the Age of Terror,” and I billed it as a memoir of my 10 years at the national level of American intelligence, my time at the National Security Agency, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence and at the Central Intelligence Agency. I didn’t mean it to be vile or vindictive, but it wasn’t very apologetic either.

Hence the title (which, by the way, was recommended by my wife). David Martin, CBS News Pentagon correspondent, got the metaphor as we were walking along the sideline at the Pittsburgh Steeler practice facility taping some coverage for the book.

“You gotta feel free to use the entire field,” I said to him and, later, to other audiences. “You don’t mark the chalklines, they come from the league office (read: appropriate authority). Your job is to use the whole field when the situation demands it. Otherwise you might be protecting yourself or your agency, but you won’t be protecting America.”

With that title and that attitude — and a tour schedule that had me hitting college campuses, editorial writers, network talk shows, Comedy Central’s “The Daily Show” and HBO’s Bill Maher show — I was prepared to defend my premise: Aggressive intelligence was a good and necessary thing. And I occasionally had to do that. But not so much.

Actually, given the tone of the presidential campaign then underway, I wound up spending at least as much time explaining that there were edges and that they had to be respected. Donald Trump, for example, was suggesting that as commander in chief he would order terrorist families to be killed. When Bill Maher mentioned that on the air, I was compelled to say that that just wasn’t going to happen, that the U.S. armed forces would simply not obey such a patently illegal order. (I thought I was pointing out something as well known and as accepted as, say, Newton’s law of gravity — you know, stuff falls.)

Turns out that wasn’t the case as the comment made news and generated a question from Fox’s Brett Baier at the next debate, where the candidate averred that the armed forces would, indeed, do such things because he was a “leader.”

The book tour also ran parallel with the exploding FBI-Apple debate over encryption, or, more specifically, whether or not the courts could compel Apple to open the (apparently) otherwise unopenable phone used by the San Bernardino terrorists.

To my mind the dispute merely highlighted what I thought was a core theme of the book: All of these decisions require tradeoffs; none of them is easy; each comes with a cost; and they rarely line up with the forces of light conveniently arrayed against the forces of darkness.

As a former director of NSA, I surprised some by shading toward Apple in the dispute, saying that on security grounds alone, I thought America was better off with encryption that had not been weakened, even if weakened in the service of legitimate counterterrorism and law enforcement needs.

That security luminaries such as Mike McConnell (director of national intelligence), Mike Chertoff (secretary of homeland security) Jim Woolsey and Dave Petraeus (former directors of CIA) and Richard Clark (White House counterterrorism chief) seemed to also trend Apple only reinforced my book tour talking point that all this was neither as simple nor as easy as it might seem, and that it deserved calm, rational and unemotional discourse.

I mostly got that in my public discussions about the book. Audiences were large and largely supportive. And when they weren’t, they generally raised their views in the form of genuine questions. I had one loud — but peaceful — protest at (of all places) my alma mater, Duquesne University in Pittsburgh. I couldn’t resist a murmured “welcome home,” as the three protesters were escorted out.

For the most part though, the public dialogues were lively, respectful, occasionally challenging and generally fun. I found a good reservoir of support out there for American espionage and its practitioners, a reality that gave me pause the longer the tour continued.

Americans are very practical folks. Accustomed to hard choices in their own lives, they are willing to give us in intelligence a lot of slack as we make the hard choices our profession demands.

All that was heartening but also a little scary. With the D.C. political rhetoric cut away, it was clear that there is a large body of people out there who instinctively both believe in and depend on the intelligence community. If nothing else, that should underscore the heavy burden on those still in the game to do what they do well — technically, operationally and legally.

So this topic deserves discussion. And introspection. And maybe even a little criticism.

I’ll offer my views on all that in subsequent columns.

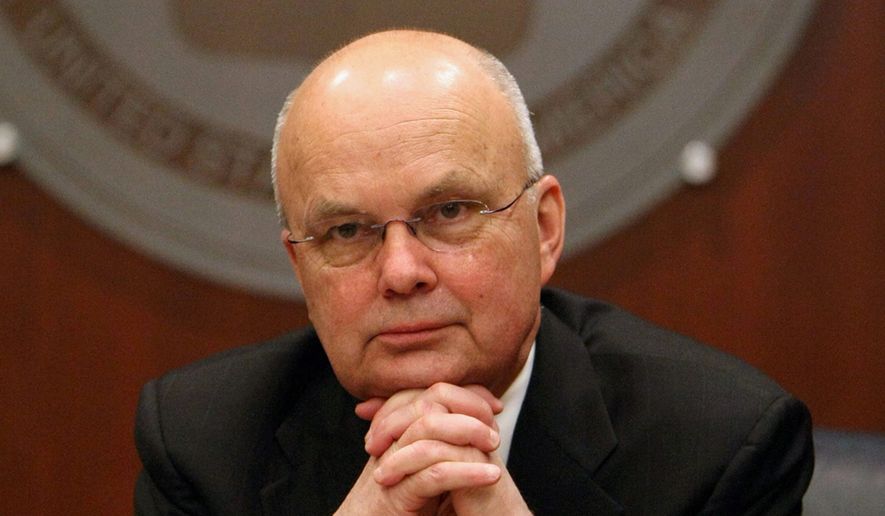

• Gen. Michael Hayden is a former director of the CIA and the National Security Agency. He can be reached at mhayden@washingtontimes.com.

• Mike Hayden can be reached at mhayden@example.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.