ANALYSIS/OPINION:

It’s hard to find the right or apt context to discuss Prince’s contribution to pop culture, not because of all the things he was but because of the things he wasn’t.

He wasn’t the voice of a generation, expressing the thoughts and dreams of an awakening audience of young folks.

He wasn’t a countercultural revolutionary, aiming to subvert and supplant the stagnant mores of a repressed society.

He wasn’t a movie or TV star embodying the physical and social expectations and standards of Hollywood’s image factory.

No, Prince did his own thing and he was his own thing — singer, musician, songwriter, performer. Many claim the term, but Prince lived it: artist.

On Thursday, Prince Rogers Nelson (his full name) was found unresponsive in his expansive Paisley Park recording studio/home in Chanhassen, Minnesota, just outside Minneapolis. He was 57.

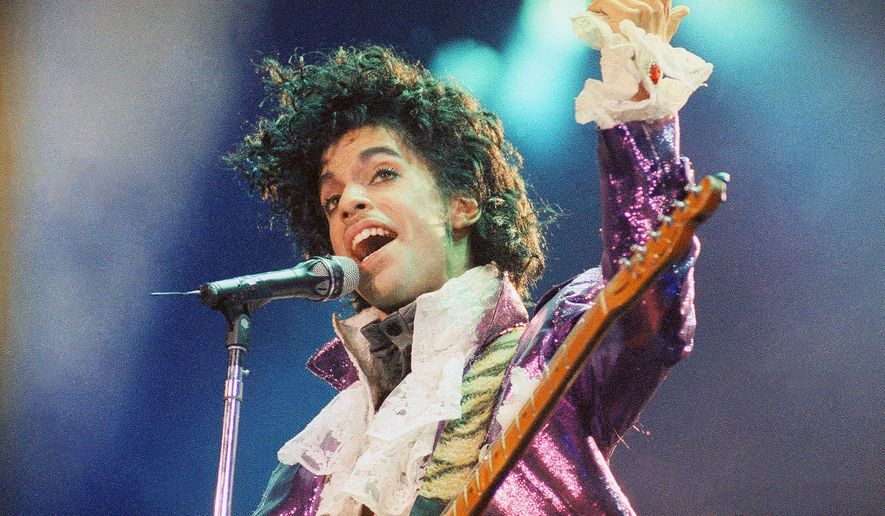

Quiet. Uncompromising. Scandalous. Spiritual. Androgynous. Disparate adjectives that barely begin to describe the unique talent that was Prince, who wove together elements of rock, soul, blues, gospel and funk to create his singular sound — sometimes salacious, sometimes sanctified, but always electrifying, energizing and engaging.

Let’s just say it: Prince was cool.

When Justin Timberlake in 2010 declared that he was bringing sexy back, Prince proclaimed that “sexy never left,” and we knew it was true.

And Prince was important. In the aftermath of last year’s riots in Baltimore, we knew we had to listen to his song written to mark the event.

So I’m kind of embarrassed to admit that my first impression of Prince and his work was “nasty.” I was 20 years old, two years removed from a Catholic education, in 1980 when his album “Dirty Mind” was released and one of my friends played it for me. To my tender ears the recording was sensuous, suggestive, risque. Songs like “Sister,” “Head” and the eponymous “Dirty Mind” were crafted to move you from the waist down — tame by today’s standards, to be sure, but back then? Nasty.

I wasn’t alone in that opinion: It was the prevailing assessment of his work. In fact, back then it was the appeal of his output. You felt you had to carry his album (featuring his lithe form in only a long jacket and a Speedo) in a brown paper wrapper and listen to it where no one else, especially adults, could hear it. Nobody was putting out anything so blatantly sexual, so creatively raw, so dangerous, so … nasty.

It’s a wonder how, from such a start, Prince managed to break into mainstream popularity, crossing not only racial barriers but also generational and socioeconomic ones. Everybody — young, old, rich, poor, black, white and purple — listened to Prince. Everybody. Even Europeans with no concept of funk. (I think it was his puffy shirts that drew them in.)

Everybody was willing to take a ride in his “Little Red Corvette,” and everybody wanted to party like it’s “1999.” And it was only 1982!

Of course, “Purple Rain” secured Prince’s success — his breakthrough 1984 album, not his breakthrough 1984 movie, which would have been a lot better if it had just been a long music video without all the “acting” and “plot.” (Prince was an icon, but he was no actor. At least the movie gave us Morris Day, for a while anyway.)

I was living in Scotland when the album was released, and suddenly BBC 1 Radio started mixing in the psychedelic soul of “When Doves Cry” and kinetic rock of “I Would Die 4 U” with the electro-pop ouvre of Depeche Mode, Blancmange and Orchestral Maneouvers in the Dark. And the nearly nine-minute rock-soul ballad “Purple Rain”? Fuhgeddaboudit. Nobody was producing anything like Prince, and only the unwise dared copy him. Anyone remember Terence Trent D’Arby? Milli Vanilli? Rockwell?

Amid all his success, Prince kept to his own vision of his artistry, changing whatever he wanted whenever he wanted, whether it was his outfits, his hair, even his band. The Revolution. The New Power Generation. Third Eye Girl.

The names change, but the sound remains the same.

• Carleton Bryant can be reached at cbryant@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.