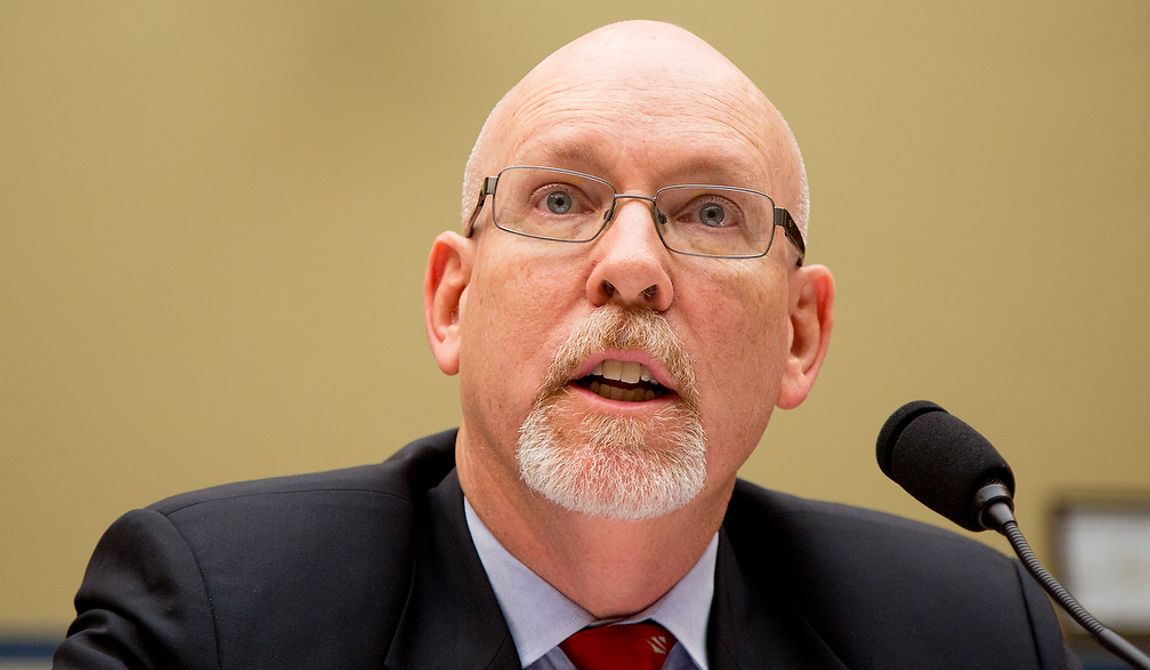

The State Department’s deputy chief of mission for the U.S. in Libya at the time of the Benghazi terrorist attack said Wednesday that the Obama administration didn’t talk to him before dubbing it a spontaneous attack spurred by an anti-Islam video, a move he said embarrassed the Libyan president and hampered the FBI investigation.

Gregory N. Hicks also said the mortar rounds that rained down on the CIA annex in Benghazi during the second phase of the attack were “terribly precise,” an immediate indication from the ground that the military-style assault was a planned attack.

“I was stunned, my jaw dropped and I was embarrassed,” he recalled Wednesday about his reaction when he saw U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Susan E. Rice appear on the Sunday TV political talk shows five days after the attack. She said the assault appeared to have grown out of spontaneous demonstrations against the video like those in other cities in the Middle East.

Mr. Hicks told the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee that he was told that the secretary of state, Hillary Rodham Clinton, was the only person empowered by law to authorize the use of U.S. diplomatic facilities in Libya last year. The buildings did not meet State Department security standards set in law after several previous terrorist attacks, culminating in the massive simultaneous suicide truck bombings of two embassies in East Africa by al Qaeda in 1998.

“It’s my understanding that since we were the sole occupants of both of those facilities, Benghazi and Tripoli, the only person who could grant waivers or exceptions to those was the secretary of state,” said Eric Nordstrom, who was regional security officer for the embassy in Libya until two months before the attack.

On Sept. 11, terrorists launched two nighttime attacks on the facility in eastern Libya, killing Ambassador J. Christopher Stevens and three other Americans — State Department computer specialist Sean Smith and former Navy SEALs Glen Doherty and Tyrone Woods.

SPECIAL COVERAGE: Benghazi Attack Under Microscope

Probe called flawed

Mr. Nordstrom, Mr. Hicks and Mark Thompson, acting deputy assistant secretary for counterterrorism, told an overflowing hearing room that the State Department probe, called an accountability review board, was incomplete and failed to interview key people on the ground.

The highly anticipated hearing showcased Republican lawmakers pushing facts that they say show the Obama administration engaged in a cover-up of major failures heading into the election. Democrats continued to dismiss questions about a topic they considered 8 months old and over.

“I don’t think there’s a smoking gun today. I don’t think there’s a lukewarm slingshot,” said Rep. Mark Pocan, Wisconsin Democrat.

Rep. Elijah E. Cummings of Maryland, the panel’s top Democrat, accused Republicans at the start of the hearing of orchestrating a campaign to smear the administration using leaks in the lead-up to the hearing.

“I am not questioning the motives of our witnesses. I am questioning the motives of those who want to use their statements for political purposes,” Mr. Cummings said.

SEE ALSO: Hillary Clinton absent from Benghazi hearing, but ‘What difference’ words were looming

But Rep. Darrell E. Issa, California Republican and the oversight panel chairman, said the hearing was needed because the Obama administration and other Democrats failed to produce basic information on the attacks and that the victims’ families deserve answers.

“These witnesses deserve to be heard on the Benghazi attacks, [and] the flaws in the accountability review board’s methodology, process and conclusion,” he said.

The accountability review board, led by former top diplomat Thomas Pickering and retired Gen. Mike Mullen, the former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, slammed bureaucrats for “grossly inadequate” security but said poor leadership could not be punished under department regulations.

It also criticized the State Department for relying too much on unreliable local militias for security in Libya and for being lulled by the absence of specific warnings of an imminent attack, rather than responding to the general security environment, which had been deteriorating for some time in eastern Libya.

Administration downplays

At the White House on Wednesday, administration spokesman Jay Carney sought to downplay the relevance of the hearings.

“This administration has made extraordinary efforts to work with five different congressional committees investigating what happened before, during and after the Benghazi attacks, including, over the past eight months, testifying in 10 congressional hearings, holding 20 staff briefings and providing over 25,000 pages of documents,” Mr. Carney said.

“As The New York Times reported this morning, much of what the witnesses were expected to raise in the hearings today has already been addressed both in hearings and in the accountability review board report,” he added.

But the review board did not consider the question of what officials said about the attacks afterward.

Mr. Hicks was closely questioned by a number of lawmakers about what he and other officials knew about the attacks in the days after it unfolded — in two stages over seven hours on the night of Sept. 11. And, in particular, if there was any indication of a protest against the anti-Islam video in Benghazi that day — as many news accounts later claimed.

“The YouTube video was a nonevent in Libya,” Mr. Hicks said. “The only report that our mission made through every channel was that there had been an attack on our consulate.”

That was why, he told lawmakers, he was so shocked to hear Mrs. Rice contradicting a statement from Libyan President Mohamad Yusef al-Magariaf, that the attack had been instigated by foreign extremists who has come to Libya for that purpose and been planning it for some time.

Mrs. Rice and her defenders have said that she relied on “talking points” prepared by intelligence officials that, even five days after the attack, reflected the continuing confusion and uncertainty about how the attack unfolded and who might have been involved.

Mr. Hicks told lawmakers that neither anyone involved in preparing the talking points, nor Mrs. Rice herself, had spoken with him before her TV appearances.

“She did not bother to have a conversation with you before she went on national television?” asked Rep. Trey Gowdy, South Carolina Republican.

“No, sir,” replied Mr. Hicks.

Questions months earlier

Mr. Nordstrom told the House committee that, more than eight months before the attacks, he asked why facilities in Tripoli and Benghazi had been occupied despite not meeting legally required security standards.

Colleagues told him in an email, “and I quote, ’It’s my understanding that Undersecretary for Management [Patrick Kennedy], agreed to the current compounds being set up and occupied, conditioned as is.’”

Mr. Nordstrom said the State Department-chartered investigation into the attacks had been interested in that correspondence, written in February 2012: “I requested, ’Is anything in writing? If so, I’d like a copy for [the] post [in Libya] so we have it handy for the ARB.’ That’s eight months before the attack.”

Mr. Nordstrom said he never got a copy of the order and he never found out who made the decision to go ahead and move staff in to buildings that did not meet security standards for issues such as setback from the public road, access controls, and blast-proof architecture.

“We did not meet any of those standards,” he said of the building in Benghazi, which was overrun and set ablaze by heavily armed extremists during the attack.

The accountability review board’s report released last year stated simply that “there was very real confusion” between diplomats on the ground and officials in Washington “over who, ultimately, was responsible and empowered to make decisions” about security there.

They said the situation was complicated by the fact that the mission in Benghazi was not even a recognized diplomatic facility. For administrative purposes, it was treated as a residential building exempt from all security standards, the report states, but it does not say on whose authority it was classified that way.

“I got no confirmation as to who made those decisions,” Mr. Nordstrom said. “No one has said they took that decision and taken responsibility for it.”

The board interviewed Mr. Kennedy and spoke with Mrs. Clinton, officials have said.

Mr. Hicks also said the U.S. military, contrary to statements made by top Pentagon brass, could have prevented the second attack phase.

Col. David Lapan, spokesman for the Joint Chiefs of Staff, told reporters that by the time the team would have left Tripoli, the second attack in Benghazi was over.

Libyans angry

Mr. Hicks added that the Libyan president had been so angered by Mrs. Rice’s comments that he was still “steamed” about it two weeks later. As a result, it took U.S. diplomats more than two weeks to get the Libyans to cooperate in bringing FBI investigators to Benghazi.

“President Magariaf was insulted in front of his own people, in front of the world. His credibility was reduced. He was angry. A friend of mine who ate dinner with him in New York during the U.N. season told me that he was still steamed about the talk shows two weeks later. And I definitely believe that it negatively affected our ability to get the FBI team quickly to Benghazi,” he said.

“It took 17-18 days for us, from that [TV] interview, to get the FBI to Benghazi,” he said. “We strung together a series of approvals from low- to mid- level officials” in the Libyan government to authorize the brief visit of the FBI to the site of the attack.

The agents were helicoptered in by the U.S. military with a large military escort, officials have said.

A State Department official denied that Mrs. Rice’s comments caused the delay in getting the FBI team to Benghazi, noting that the agents were issued visas the day after the TV talk shows and arrived the day after that.

• Shaun Waterman can be reached at swaterman@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.